16.1. Exceptions¶

Errors are a part of coding. Occasionally, we make mistakes as programmers. However, we are always trying to fix those mistakes by reading different resources, examining a list of error messages (also called the stacktrace), or asking for help.

Earlier in this course, we learned about two different types of errors: compiler and logic. A logic error is when your program executes without breaking, but doesn’t behave the way you thought it would. These logic errors usually require you to consider how you are going about solving the issue to resolve. Compiler errors are when your program does not run correctly, and an exception is raised.

Maybe you see the term “exception” and instinctively groan or roll your eyes? Isn’t programming only enjoyable when it works? While it would be nice if our code ran perfectly every time, exceptions are a key component of a healthy codebase. When an exception arises, we, as programmers, can use the info to debug our code. For our fellow programmers, the exceptions we provide give them necessary intel on how our app runs and is meant to be used.

Like most programming languages, C# includes exceptions and exception handling tooling. Some exception objects are provided by .NET itself. Other exception objects we may get from external C# libraries. We may even write these objects ourselves.

Exceptions in C# are objects derived from the System.Exception class.

You see exception objects at runtime when some event takes place outside of the expected flow of our code.

When you want to explicitly call an exception in your code, you do so

with the throw keyword.

16.1.1. When Exceptions Arise¶

You may have seen exceptions in C# or another programming language already, perhaps in one of these scenarios:

Failure to connect to services external to your application, such as a database or Application Program Interface (API).

Failure to read or write to or from a file.

Failure to convert data, such as trying to convert something like

"dog"to aninttype.Failure to reach an actual object.

Note

This last scenario is a null pointer. This is an object reference that doesn’t actually contain an object.

Let’s look at an example where exceptions would help with the overall output of code.

Here is a block of code that prints out a Fahrenheit temperature value.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine("Please enter a Fahrenheit temperature value");

string inputValue = Console.ReadLine();

double inputTemp = Double.Parse(inputValue);

//Test 1: userTemp set to 73

Temperature userTemp = new Temperature(inputTemp);

//re-run program

//Test 2: userTemp set to -8200

Temperature userTemp = new Temperature(inputTemp);

}

}

public class Temperature

{

public Temperature(double fahrenheit)

{

Console.WriteLine("You entered " + fahrenheit + " degrees F.");

}

}

|

It is very simple. Provide the value, print sentence. Great. However, Fahrenheit cannot go beyond -459.67 degrees. That is absolute zero, the equivilant to 0 degrees Kelvin.

So, why would we want a user to be able to go past absolute zero in our program, when it is not physically possible? No one wants invalid data. This would be a good place to throw an exception.

16.1.2. Throwing An Exception¶

In most programming languages, when the compiler or interpreter encounters code it doesn’t know how to handle, it throws an exception. This is how the compiler notifies the programmer that something has gone wrong. Throwing an exception is also known as raising an exception.

C# gives us the ability to raise exceptions using the throw statement by using the System.Exception class.

One reason to throw an exception is if your code is being used in an unexpected way.

In our temperature app, we don’t want the user to go past absolute zero, so we can thrown an exception that will inform us of the issue.

The ArgumentOutOfRangeException will be a good fit for our exception.

The question is where to validate our data?

It would make sense to have an issue arrise at instantiation of a new Temperature object.

That would prevent any objects containing invalid data be created at all.

We should throw our exception in the constructor.

If the data is good, a new object is built. If not, an exception will be thrown.

The Exception class contains many built-in exception types that you can use in your code.

We are going to use ArgumentOutOfRangeException since we want to create limitations on the range of values allowed in our program.

ArgumentOutOfRangeException is its own class, so we will need to instantiate it after the keyword throw.

Think of it as throwing the new excpetion.

In this example, we provided our message directly as a parameter.

When the compiler encounters the exception, our message will print in the stack.

This allows the developer to see the exception, but will not print it to the console.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | public class Temperature

{

public static double absoluteZero = -459.67;

public Temperature(double fahrenheit)

{

if(fahrenheit < absoluteZero)

{

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("Value is below absolute zero.");

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("You entered " + fahrenheit + " degrees F.");

}

}

}

|

ArgumentOutOfRangeException is not able to read your mind, you will have to provide logic that creates a reason for the exception to be thrown or not.

In this example, we created a static field absoluteZero to be our point of comparison.

The constructor will evaluate the validity of incoming input with an if/else block.

This example is also provided in the Unit1-TempExceptions project in this repo.

Clone this repo and build along.

The program now provides a plan for what to do in the event that bad data is passed into a class’s field. Imagine that a user or fellow programmer unintentionally sets a Fahrenheit value outside of the appropriate range.

Try this yourself to witness the breaking exception:

Example

Input:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | Console.WriteLine("Please enter a Fahrenheit temperature value");

string inputValue = Console.ReadLine();

double inputTemp = Double.Parse(inputValue);

//Test 1: userTemp set to 73

Temperature userTemp = new Temperature(inputTemp);

//re-run program

//Test 2: userTemp set to -8200

Temperature userTemp = new Temperature(inputTemp);

|

Output:

//Test 1 output

You entered 73 degrees F.

//Test 2 output

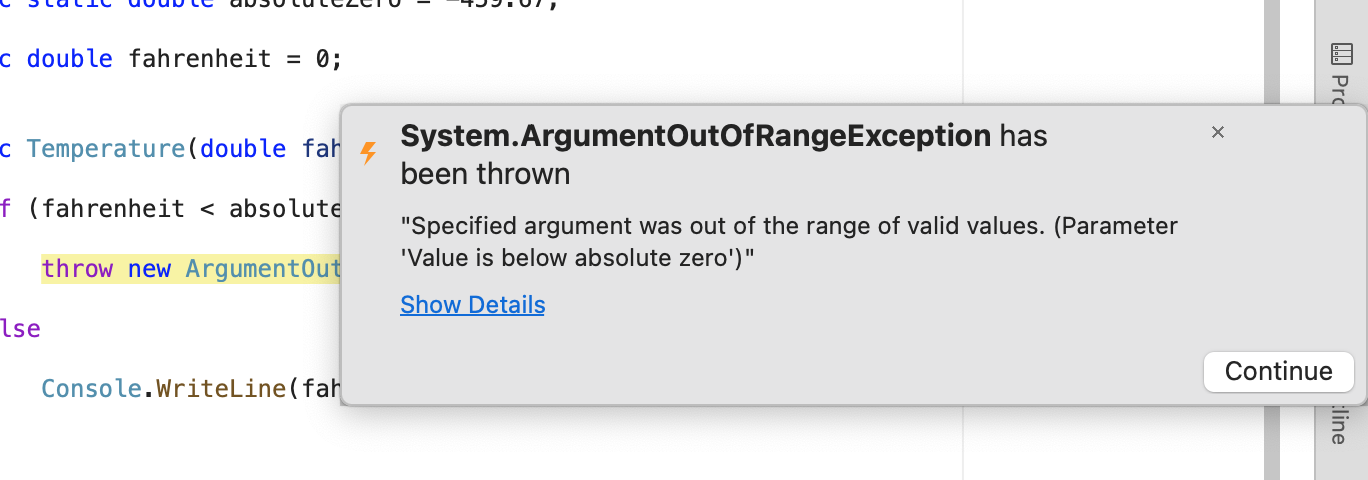

System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException: Specified argument was out of the range of valid values.

(Parameter 'Value is below absolute zero') at TempsException.Temperature..ctor(Double fahrenheit)

in /Users/courtneyfrey/Projects/TempsExceptions/TempsException/TempsException/Temperature.cs:line 13

Above, the Temperature constructor predictably sets the Fahrenheit value of Test 1 on Line 6 and throws an exception when provided a Fahrenheit value outside of the appropriate range with Test 2. We don’t see any results of the print statement on for Test 2 since the exception has caused the program to stop running.

When we throw an exception like in the example above, we flag the anomalous circumstance. If we choose to do nothing when the exception is thrown, the program will stop and a record of the exception can be found in the stack trace.

You may also see a pop-up window telling you about the exception.

Alternatively, we can handle an exception and offer an alternative action, bypassing the need to stop the program. We’ll cover how to handle exceptions on the next page.

This is a common reason to include exception handling in your code. User input opens the door to a variety of erroneous figures and good programs account for this uncertainty. Without exceptions in these circumstances, a small typo could lead to any number of errors down the stack trace.

16.1.3. When to Use Exceptions¶

It is wise to use an exception if you find that there is some level of chance involved in your program. This could be a situation where a variable is dependent on user input or a connection to another service.

You may want to address those uncertainties in a different fashion. With our temperature app for example, rather than throwing an exception, we can add a conditional statement to tell the user not to set the Fahrenheit value to an unacceptable level. This is perfectly acceptable if the app in production allows for such a message. As you will see on the next page, exception handling works very similarly to conditional statements like this.

There are many places where user-directed error messages simply won’t be appropriate. For example, what if the value being set doesn’t come from a user but from a different method in the program? In a situation like this, where the anomaly is not visible to the user, an exception conveys the issue to fellow programmers who are using our codebase.

Or another hypothetical. What if managing the variety of errors that may arise is outside the scope of the project? In these cases where we do not, or cannot, make up for the edge cases with coded solutions, we can throw an exception. Exceptions are an informed way to convey the constraints of your program.

16.1.4. Check Your Understanding¶

Question

What is the action of invoking an exception called?

excepting

catching

throwing

handling

Question

True/False: Encountering an exception will always result in terminating a running program.

True

False