Coding together allows you to work as a team so you can build bigger projects faster.

In this studio, we will practice the common Git commands used when multiple people work on the same code base.

You and a partner will begin by coding in tag-team shifts. By the end of the task you should have a good idea about how to have two people work on the same code at the same time. You will learn how to:

This lesson reinforces:

The instructor will discuss why GitHub is worth learning. You already know how to use a local Git repository with one branch, giving you the ability to move your code forward and backward in time. Working with branches on GitHub extends this ability by allowing multiple people to build different features at the same time, then combine their work. Pull requests act as checkpoints when code flows from branch to branch.

Students must pair off for this exercise. If you have trouble finding a partner, ask your TA for help.

We are going to simulate a radio conversation between the shuttle pilot and mission control.

First, find a new friend to share the activity.

You and your partner will alternate tasks, so designate one of you as Pilot and the other as Control. Even when it is not your turn to complete a task, read and observe what your partner is doing to complete theirs. The steps here mimic how a real-world collaborative Git workflow can be used within a project.

Warning

As you go through these steps, you'll be working with branches. It's very

likely you will make changes to the code only to realize that you did so in the

wrong branch. When this happens (and it happens to all of us) you can use

Git stash to cleanly move your changes to another branch. Read about how

to do so in our Git Stash tutorial.

Note

Be careful if you try to use copy/paste with the git commands! The

$ symbols in the screenshots represent to the prompts in the terminal.

They are NOT part of the commands.

Control: Navigate to your development folder. Enter the following 3 commands to create a new project.

$ mkdir communication-log

$ cd communication-log

$ git init

In that directory, open a new file index.html in the editor of your choice.

Paste in this code:

1<html>

2 <body>

3 <p>Radio check. Pilot, please confirm.</p>

4 </body>

5</html>

Let's check that our html looks okay by opening it in a browser. Do this by

selecting File > Open File in your web browser, and navigating to the

location of your new HTML file. The URL will look something like this:

file:///Users/username/Development/communication-log/index.html.

Once you've checked this file in the browser, let's stage and commit it.

First, check the status.

$ git status

On branch main

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "Git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

index.html

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

The output shows is that index.html is not staged. Let's add

everything in this directory, then check the status again.

$ git add .

$ git status

On branch main

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: index.html

The output tells us that the file is staged. Now let's commit. After

that, we can see a record of our progress by using git log.

$ git commit -m 'Started communication log.'

[main (root-commit) e1c1719] Started communication log.

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 index.html

$ git log

commit 679de772612099c77891d2a3fab12af8db08b651

Author: Cheryl <[email protected]>

Date: Wed Apr 5 10:55:56 2017 -0500

Started communication log.

Great! We've got our project going locally, but we're going to need to make it accessible for Pilot also. Let's push this project up to GitHub.

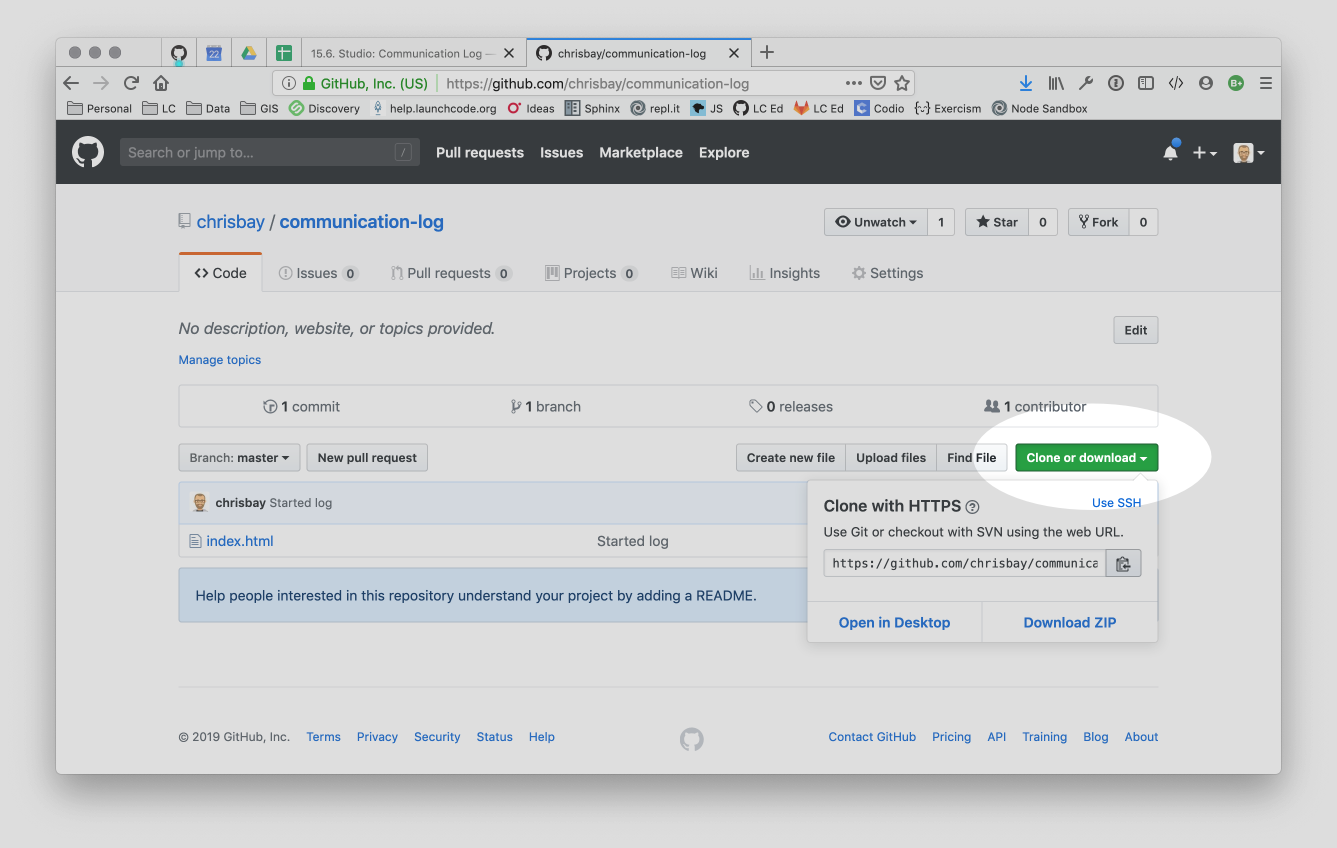

Pilot: Go to Control's GitHub profile and find the communication-log repo. Click on the green Clone or download button. Use HTTPS (not SSH). Copy the url to your clipboard.

Cloning a repository in GitHub¶

In your terminal, navigate to your development folder and clone down the repo. The command should look something like this.

$ git clone https://github.com/chrisbay/communication-log.git

Now you can respond to Control! Open the index.html file in your editor and

add your response to mission control. Be creative, the communication can go

anywhere! Just don't ask your partner what you should write. After you finish,

commit your change.

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working directory clean

$ git add index.html

$ git commit -m 'Added second line to log.'

Now we need to push up your changes so Control can use them as well.

$ git push origin main

ERROR: Permission to chrisbay/communication-log.git denied to pilot.

fatal: Could not read from remote repository.

Please make sure you have the correct access rights

and the repository exists.

Great error message! It let us know exactly what went wrong: Pilot does not have security permissions to write to Control's repo. Let's fix that.

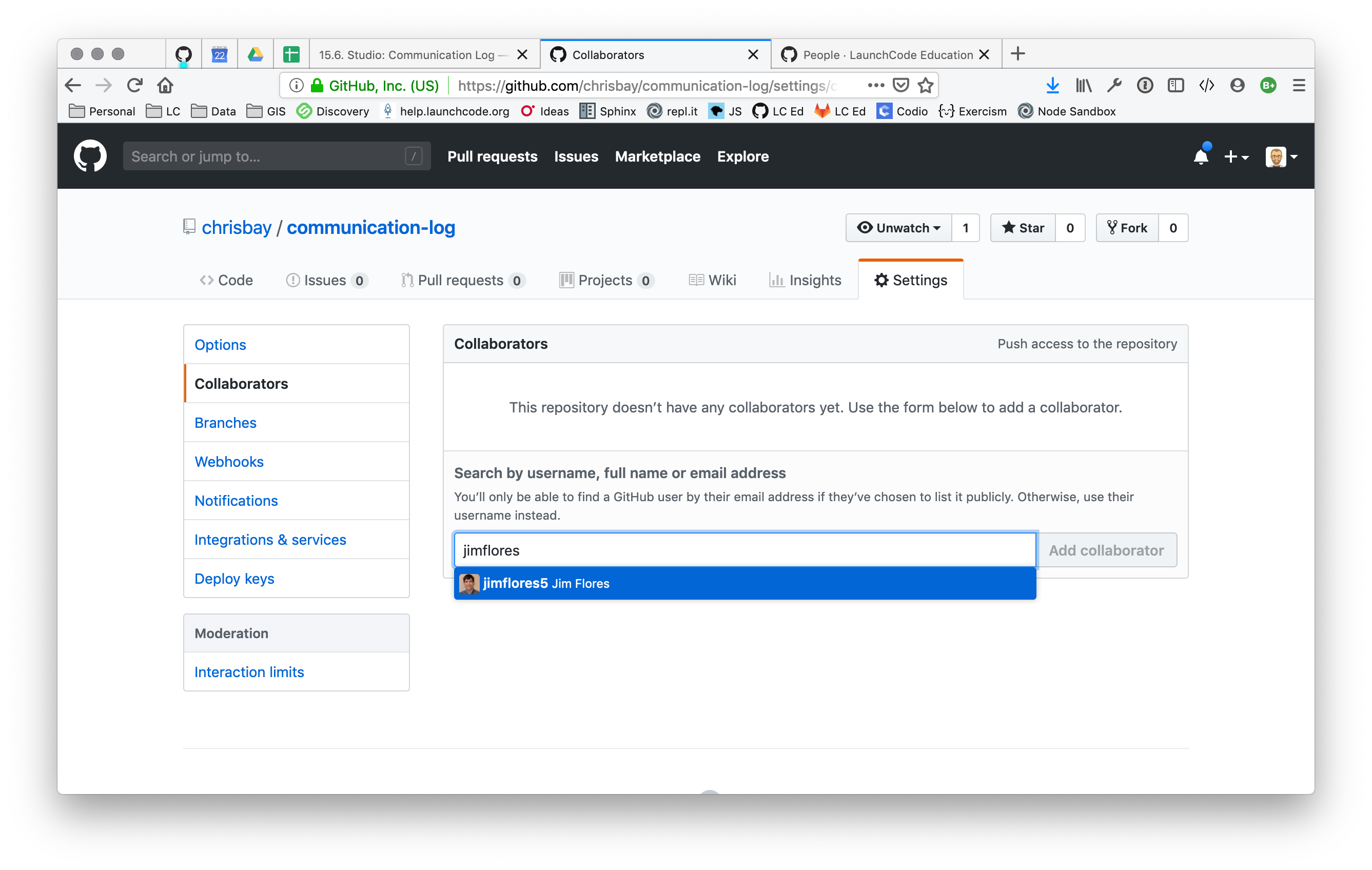

Control: In your web browser, go to your communication-log repo. Click

the Settings button then click on Collaborators. Enter in Pilot's GitHub

username and click Add Collaborator.

Add a collaborator to your repo in GitHub¶

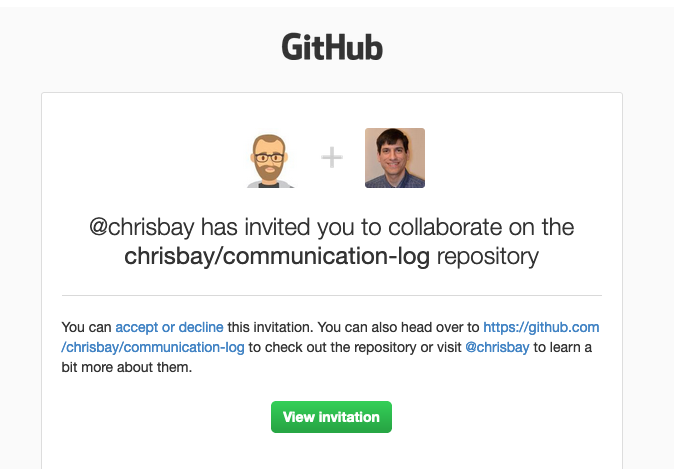

Pilot: You should receive an email invitation to join this repository. View and accept the invitation.

Note

If you don't see an email (it may take a few minutes to arrive in your inbox), check your Spam folder. If you still don't have an email, visit the repository page for the repo that Control created (ask them for the link), and you'll see a notification at the top of the page.

Invited to collaborate email in GitHub¶

Now let's go enter that command again to push up our code.

$ git push origin main

Counting objects: 9, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (9/9), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 1.01 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 9 (delta 8), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (8/8), completed with 8 local objects.

To [email protected]:chrisbay/communication-log.git

511239a..679de77 main -> main

Anyone reading the HTML through GitHub's browser interface should now see the new second line.

Control: You might notice you don't have the second line of code in your copy of the project on your computer. Let's fix that. Go to the terminal and enter this command to pull down the updated code into your local git repository.

$ git pull origin main

remote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 1), reused 3 (delta 1), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From github.com:chrisbay/communication-log

e0de62d..e851b7e main -> origin/main

Updating e0de62d..e851b7e

Fast-forward

index.html | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now, in your editor, add a third line to the communication. Then add, commit, and push it up.

You can have your story go anywhere! Try to tie it in with what the pilot wrote, without discussing with them any plans on where the story will go.

Pilot: You might notice now you don't have the third line on your computer. Go to the terminal and enter this command to pull in the changes that Control just made.

$ git pull origin main

remote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 1), reused 3 (delta 1), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From github.com:chrisbay/communication-log

e851b7e..167684c main -> origin/main

Updating e851b7e..167684c

Fast-forward

index.html | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now add a fourth line to the log. Again, be creative, but no planning!

Then add, commit, and push your change.

You can both play like this for a while! Feel free to repeat this cycle a few times to add to the story.

This workflow is a common one in team development situations. You might wonder, however, if professional developers sit around waiting for their teammates to commit and push a change before embarking on additional work on their own. That would be a drag, and thankfully, there is a nice addition to this workflow that will allow for simultaneous work to be carried out in a reasonable way.

Pilot: While Control is working on an addition to the story, let's make

another change simultaneously. In order to do that, we'll create a new branch.

Recall that a branch is a separate "copy" of the codebase that you can commit

to without affecting code in the main branch.

$ git checkout -b open-mic

Switched to a new branch 'open-mic'

This command creates a new branch named open-mic, and switches your local

repository to use that branch.

Create a new file named style.css and add the following rules:

1body {

2 color: white;

3 background-color: black;

4}

Then link it in index.html. It should look something like this:

1<html>

2 <head>

3 <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="style.css">

4 </head>

5 <body>

6 <p>Radio check. Pilot, please confirm.</p>

7 ... your content here

8 </body>

9</html>

Now stage and commit these changes.

$ git add .

$ git commit -m 'Added style.css'

$ git push origin open-mic

Note that the last command is a bit different than what we've used before

(git push origin main). The final piece of this command is the name of

the branch that we want to push to GitHub.

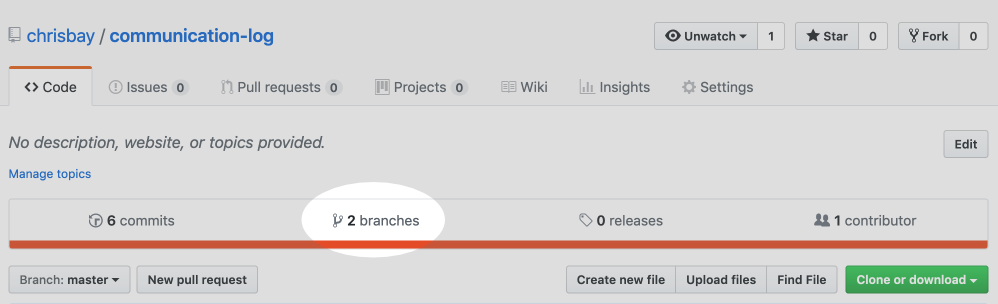

You and your partner should both now see a second branch present on the GitHub project page. To view branches on GitHub, select Branches from the navigation section just below the repository title.

Branches Button in GitHub¶

In your terminal, you can type this command to see a list of the available branches:

$ git branch

* open-mic

main

Note that creating and being able to see a branch in your local repository via this command does NOT mean that the branch is on GitHub. You'll need to push the branch for it to appear on GitHub.

Note

The * to the left of open-mic indicates that this is the active branch.

Great! Now let's show the other player your work in GitHub and ask them to merge it in to the main branch.

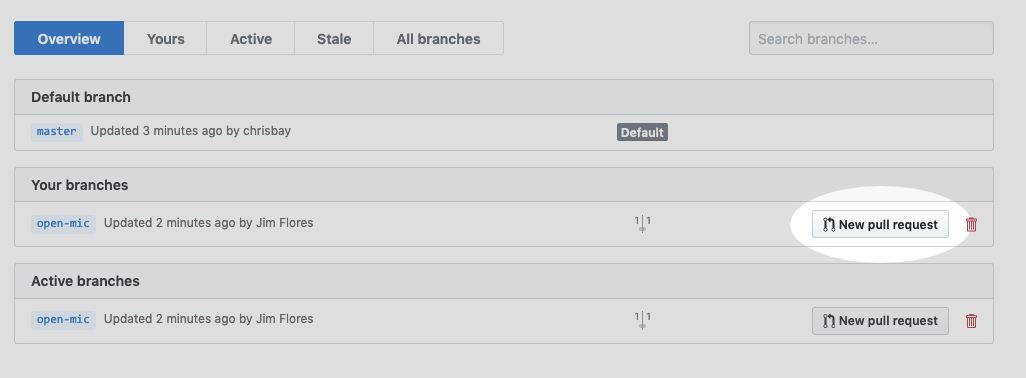

Pilot: If you haven't already, in your browser, go to the GitHub project and click on Branches and make sure you see the new branch name, open-mic.

Branches Page in GitHub¶

Click New Pull Request to begin the process of requesting that your changes

in the open-mic branch be incorporated into the main branch. Add some

text in the description box to let Control know what you did and why.

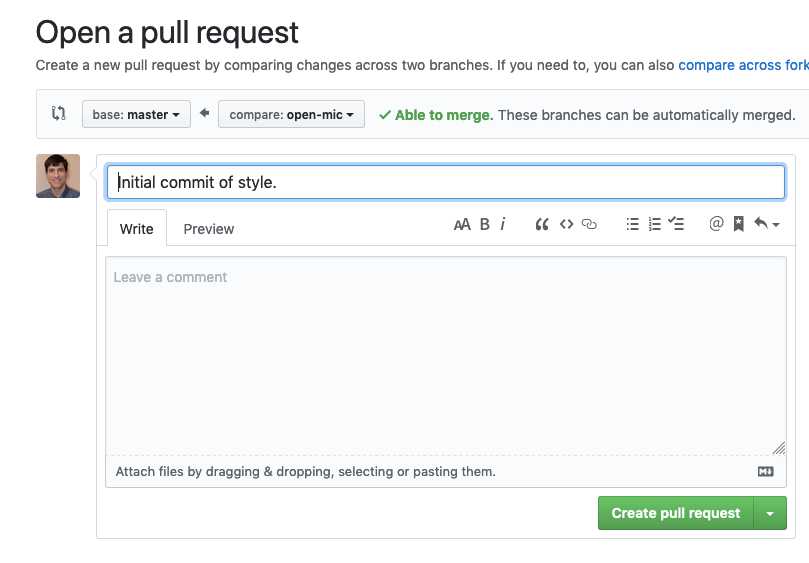

Note that the branch selected in the base dropdown is the one you want to merge into, while the selected branch in the compare dropdown is the one you want to merge from.

Open a PR in GitHub¶

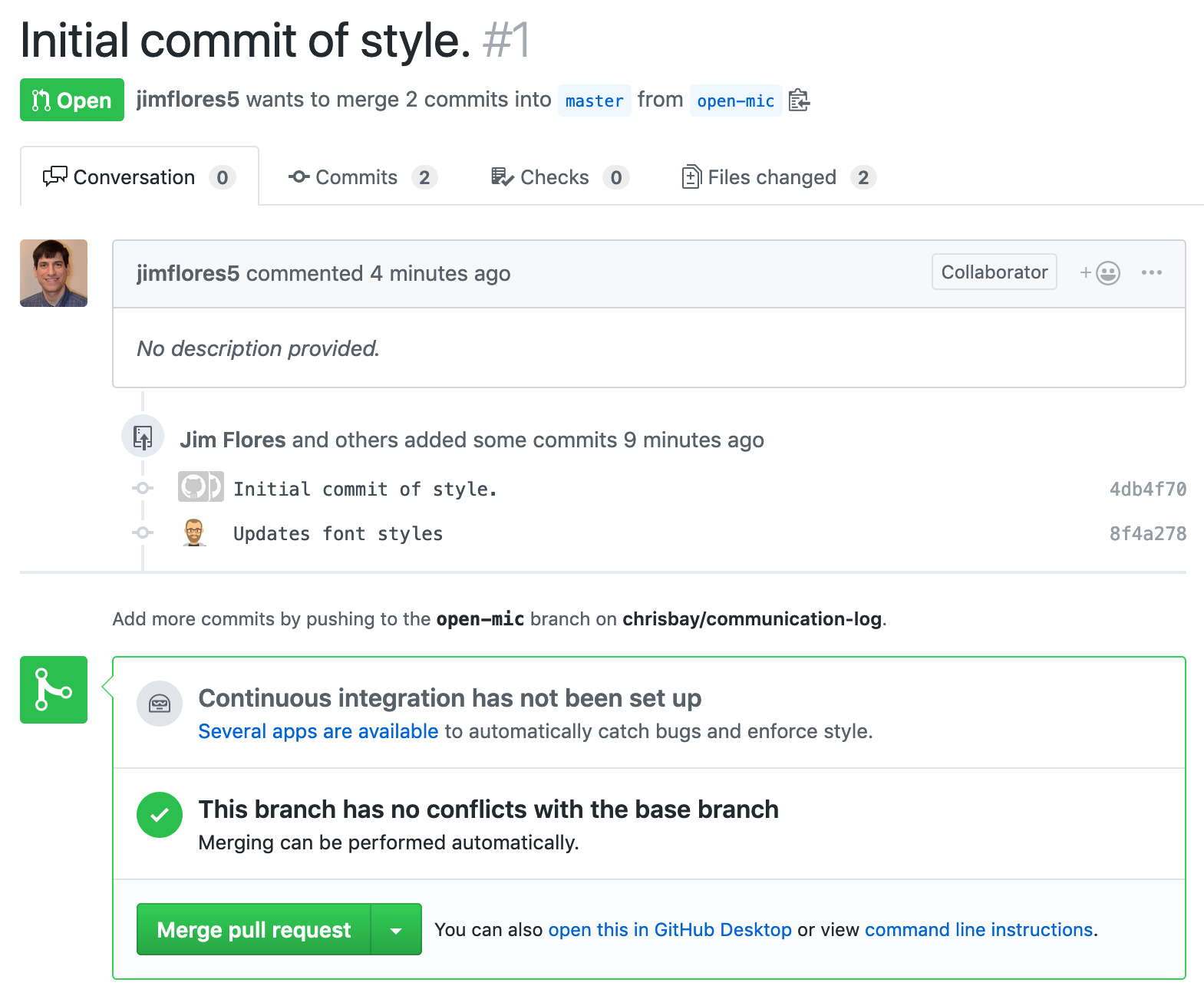

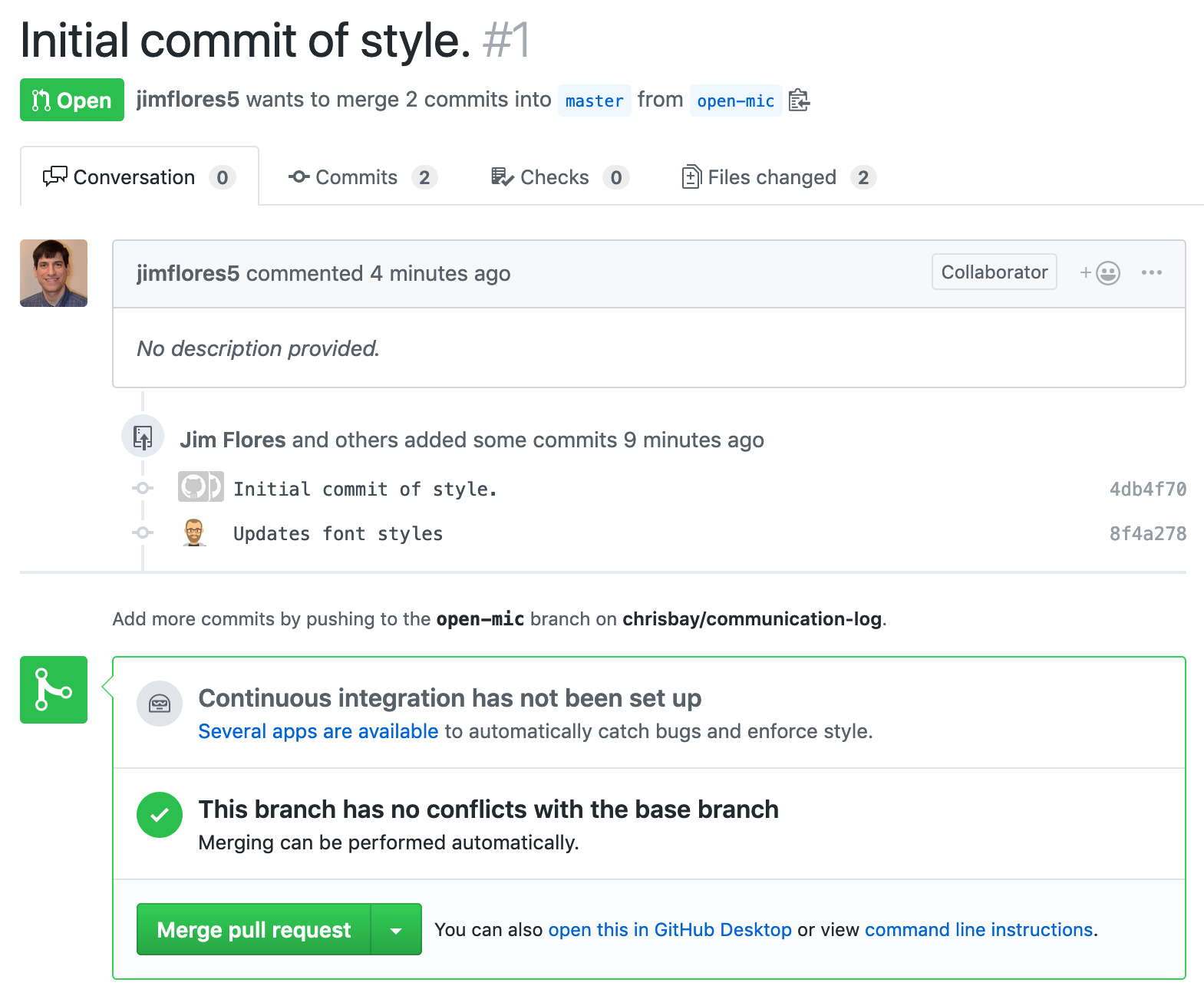

This is what an opened pull request looks like:

An open PR in GitHub¶

Control: You will notice that you do not see the new style.css file

locally. Type this command to see what branches are on your local computer:

$ git branch

* main

If you want to work with the branch before merging it in, you can do so by typing these commands:

$ git fetch origin open-mic

...

$ git branch

open-mic

* main

$ git checkout open-mic

Switched to branch 'open-mic'

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/open-mic'.

Make a change, commit, and push this branch--you will see that the pull request in GitHub is updated to reflect the changes you added. The context in the description box is NOT updated, however, so be sure to add comments to the pull request to explain what you did and why.

Now switch back to the main branch:

$ git checkout main

Switched to branch 'main'

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

You will see your files no longer have the changes made in the open-mic

branch. Let's go merge those changes in, so that the main branch adopts

all the changes in the open-mic branch.

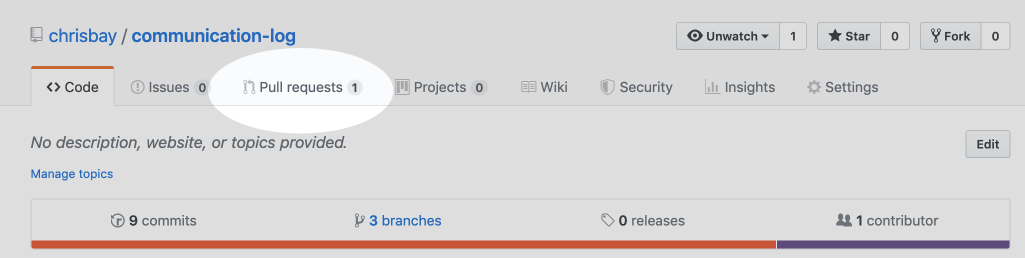

Control: Go to the repo in GitHub. Click on Pull Requests.

PR Open in GitHub¶

Explore this page to see all the information GitHub shows you about the pull request.

Merge a Pull Request in GitHub¶

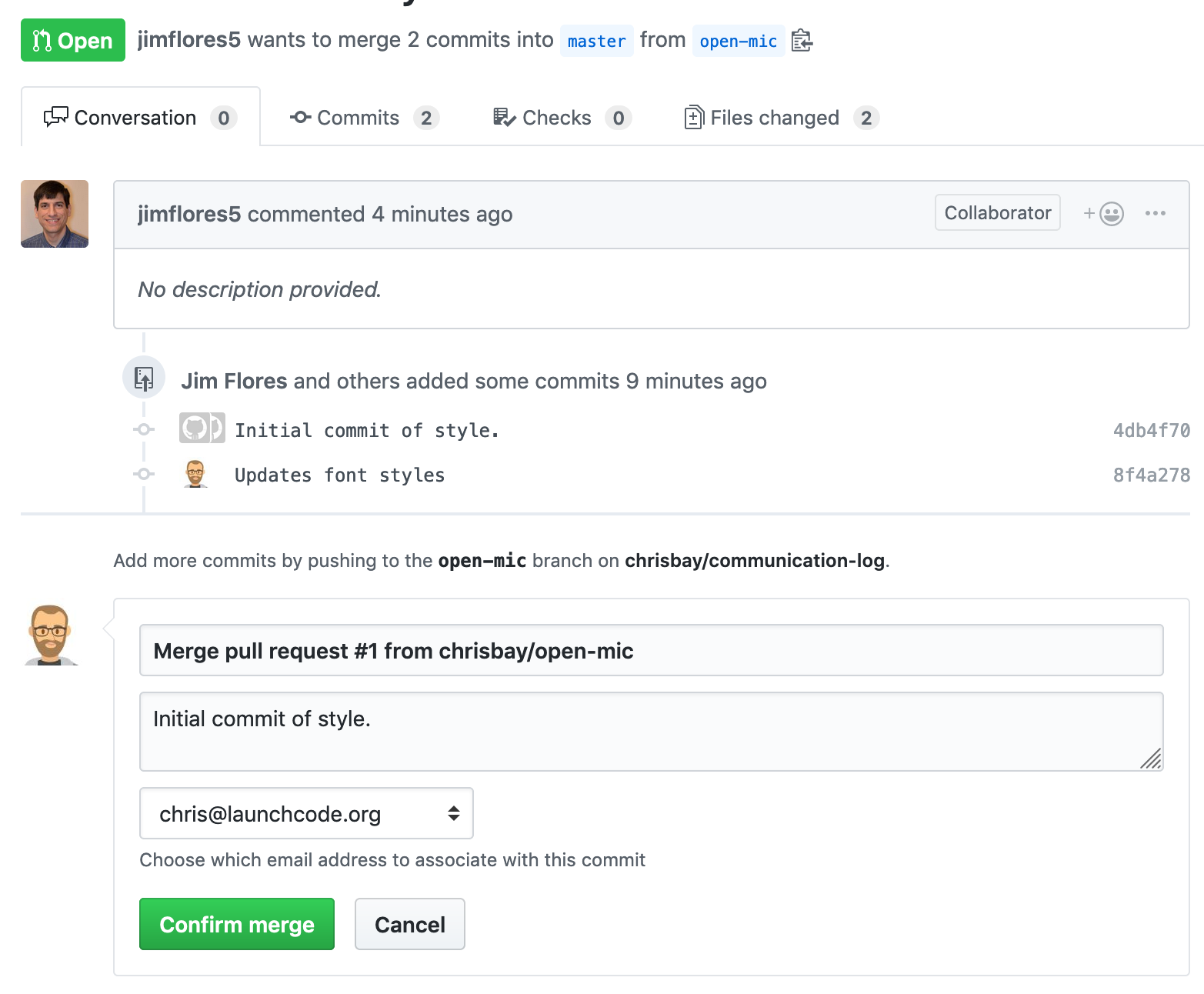

When you're happy with the changes, merge them in. Click Merge Pull Request then Confirm Merge.

Confirm PR Merge in GitHub¶

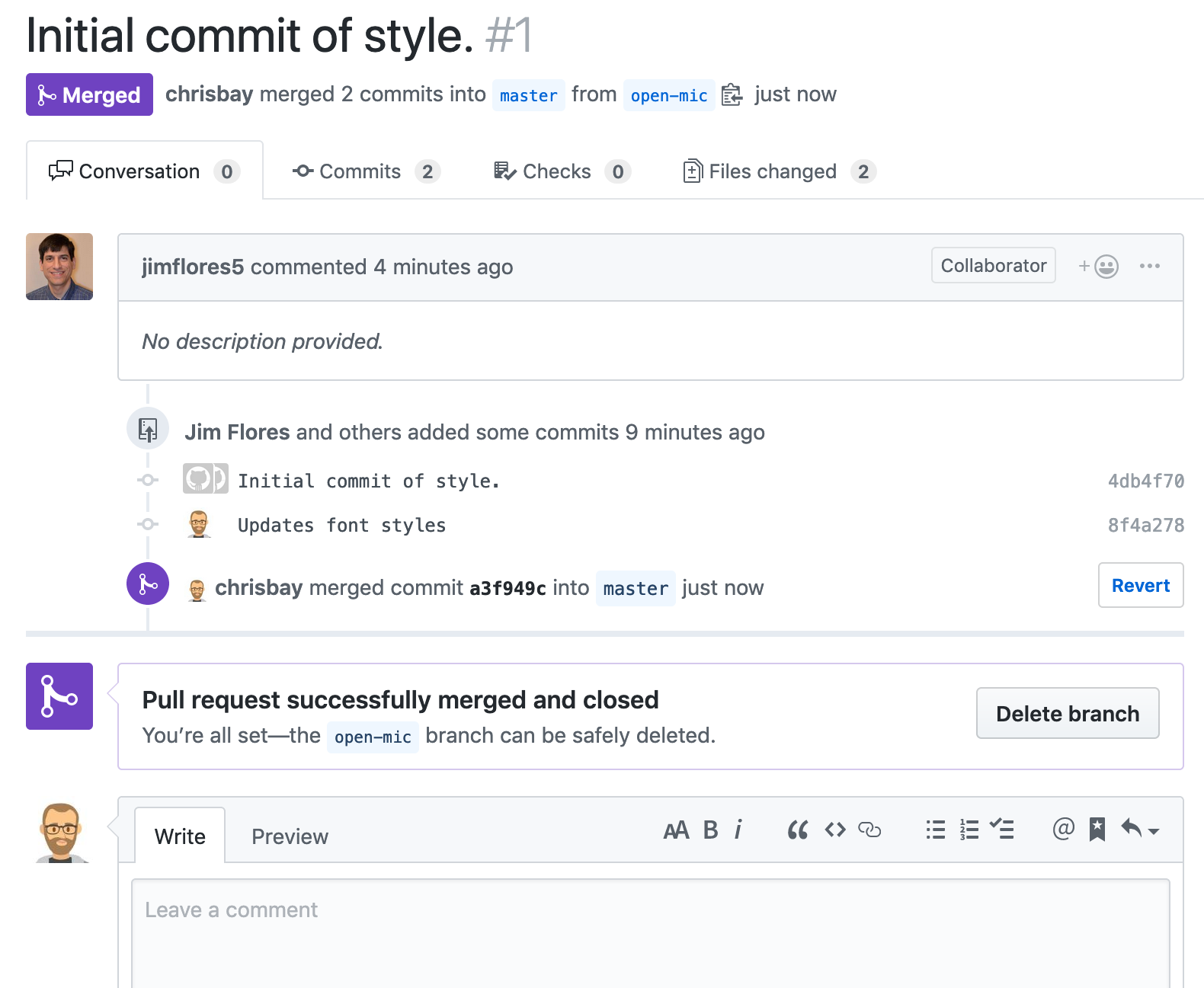

Upon a successful merge, you should see a screen similar to the following:

PR Merged in GitHub¶

The changes from open-mic are now in the main branch, but only in

the remote repository on GitHub. You will need to pull the updates to your

main for them to be present locally.

$ git checkout main

$ git pull origin main

Git is able to merge these files on its own.

When collaborating on a project, things won't always go smoothly. It's common for two people to make changes to the same line(s) of code, at roughly the same time, which will prevent Git from being able to merge the changes together.

Git Merge Conflicts¶

This isn't such a big deal. In fact, it's very common. To see how we can handle such a situation, we'll intentionally create a merge conflict and then resolve it.

Pilot: Let's change something about the style file. Our HTML is looking pretty plain, so let's pick a nice font and add some margins.

First, switch back to the main branch.

$ git checkout main

Let's change our font. To do so, add this link to your index.html file,

right after the first stylesheet link:

<link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Satisfy" rel="stylesheet">

And spice up your style.css file to look like this:

1body {

2 color: white;

3 background-color: #333;

4 font-size: 150%;

5 font-family: 'Satisfy', cursive;

6 margin: 5em 25%;

7}

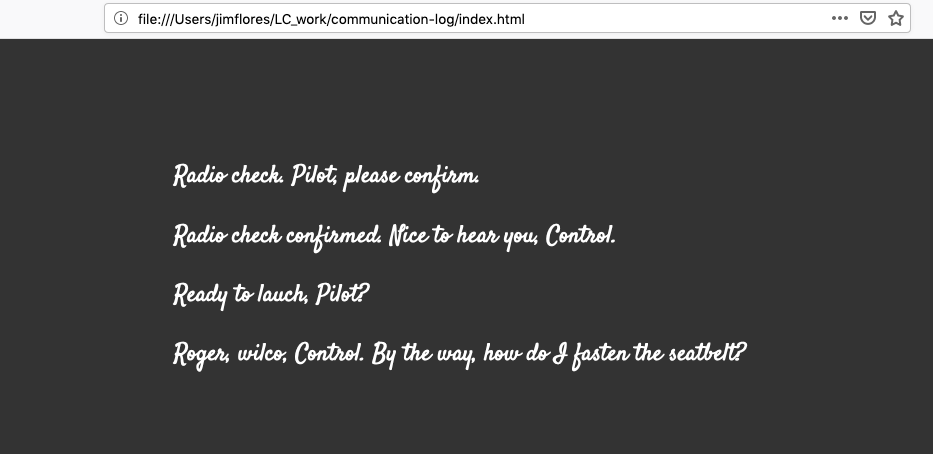

The result:

Satisfying!¶

Stage and commit your changes and push them up to GitHub. If you don't remember

how to do this, follow the instructions above. Make sure you're back in the

main branch! If you're still in open-mic, then your changes will be

isolated, and you won't get the merge conflict you need to learn about.

Meanwhile...

Control: Let's change something about the style file that Pilot just edited. Change it to look like this:

1body {

2 color: white;

3 background-color: black;

4 font-family: 'Sacramento', cursive;

5 font-size: 32px;

6 margin-top: 5%;

7 margin-left: 20%;

8 margin-right: 20%;

9}

Don't forget to link the new font in your index.html file, after the other

link:

<link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Sacramento" rel="stylesheet">

Commit your changes to branch main.

Control: Try to push your changes up to GitHub. You should get an error message. How exciting!

$ git push origin main

To [email protected]:chrisbay/communication-log.git

! [rejected] main -> main (fetch first)

error: failed to push some refs to '[email protected]:chrisbay/communication-log.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do

hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing

hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes

hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

There's a lot of jargon in that message, including some terminology we haven't encountered. However, the core of the message is indeed understandable to us: "Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do not have locally." In other words, somebody (Pilot, in this case), pushed changes to the same branch, and you don't have those changes on your computer. Git will not let you push to a branch in another repository unless you have incorporated all of the work present in that branch.

Let's pull these outstanding changes into our branch and resolve the errors.

$ git pull

remote: Counting objects: 4, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 4 (delta 1), reused 4 (delta 1), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (4/4), done.

From github.com:chrisbay/communication-log

7d7e42e..0c21659 main -> origin/main

Auto-merging style.css

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in style.css

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Since Pilot made changes to some of the same lines you did, Git was unable to automatically merge the changes.

The specific locations where Git could not automatically merge files are

indicated by the lines that begin with CONFLICT. You will have to edit

these files yourself to incorporate Pilot's changes. Let's start with

style.css.

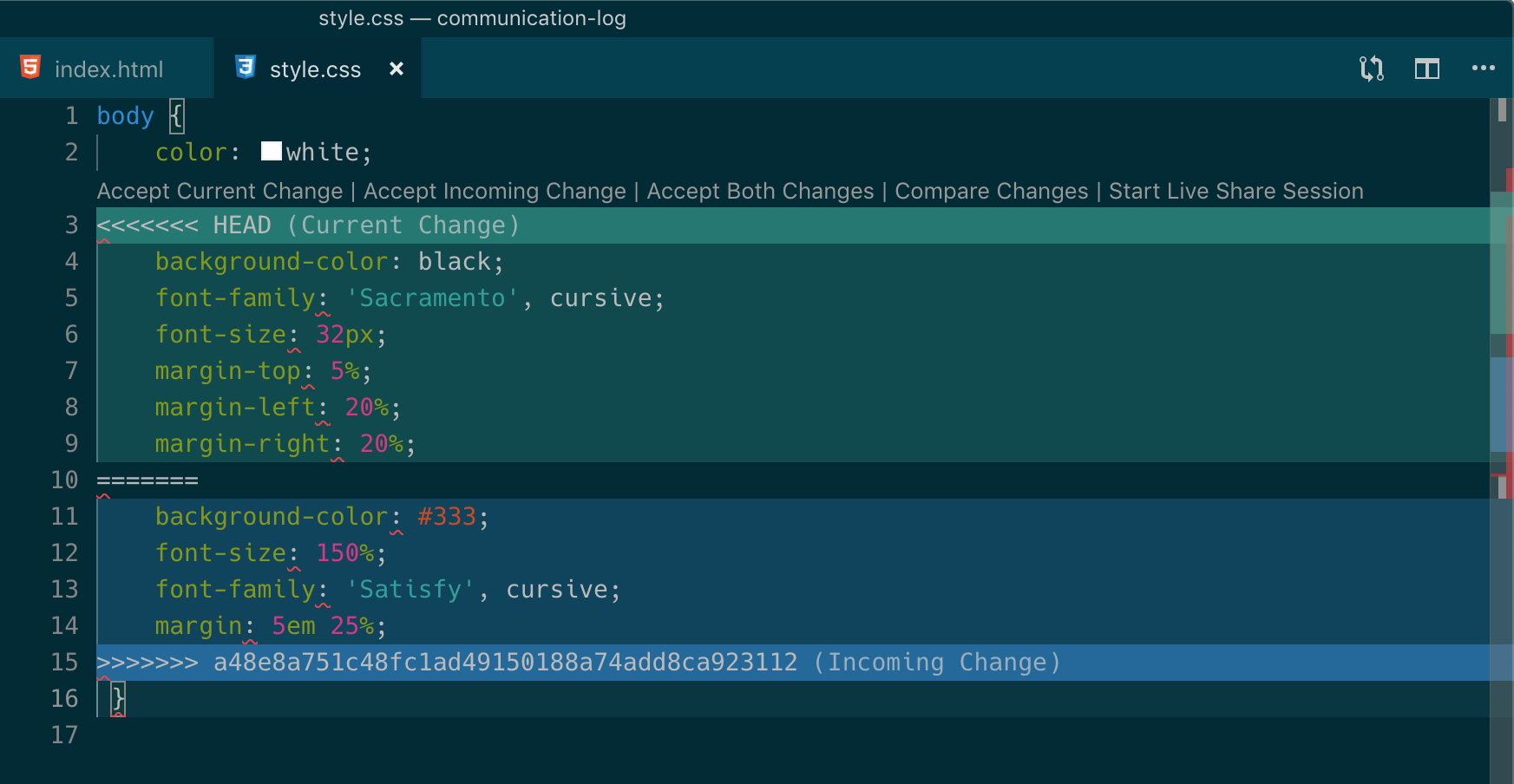

Merge conflicts in style.css, viewed in VS Code¶

At the top and bottom, there is some code that could be merged without issue.

Between the <<<<<<< HEAD and ======= symbols is the version of the code

that exists locally. These are your changes.

Between ======= and >>>>>>> a48e8a75...

are the changes that Pilot made (the hash a48e8a75... will be unique to

the commit, so you'll see something slightly different on your screen).

Let's unify our code. Change the CSS to look like this, making sure to remove the Git markers so that only valid CSS remains in the file.

1body {

2 color: white;

3 background-color: black;

4 font-family: 'Sacramento', cursive;

5 font-size: 150%;

6 margin: 5em 25%;

7}

Tip

Like many other editors, VS Code provides fancy buttons to allow you to resolve individual merge conflicts with a single click. There's nothing magic about these buttons; they do the same thing that you can do by directly editing the file.

You will need to do the same thing for the index.html file. You only need

the link for the Sacramento font, not the Satisfy font. Then stage, commit, and

push your changes; you should not see an error message this time.

Pilot: Meanwhile, Pilot is sitting at home, minding their own business. A

random git status seems reassuring:

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Your local Git thinks the status is quo. Little does it know that up at GitHub,

the status is not quo. We'd find this out by doing either a git fetch, or

if we just want the latest version of this branch, git pull:

$ git pull

remote: Counting objects: 13, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (8/8), done.

remote: Total 13 (delta 4), reused 13 (delta 4), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (13/13), done.

From Github.com:chrisbay/communication-log

0c21659..e0de62d main -> origin/main

Updating 0c21659..e0de62d

Fast-forward

index.html | 3 ++-

style.css | 4 ++--

2 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)

Great Scott! Looks like Control changed both index.html and style.css.

Note that Pilot didn't have to deal with the hassle of resolving merge

conflicts. Since Control intervened, Git assumes that the team is okay with the

way they resolved it, and fast forwards our local repo to be in sync with the

remote one. Let's look at style.css to make sure:

1body {

2 color: white;

3 background-color: black;

4 font-family: 'Sacramento', cursive;

5 font-size: 150%;

6 margin: 5em 25%;

7}

Let's turn the tables on the steps we just carried out, so Pilot can practice resolving merge conflicts.

Merge conflicts are a part of the process of team development. Resolve them carefully in order to avoid bugs in your code.