As mentioned in the terminal chapter, the essence of the command line is text. Since this is quite different from how many may be used to using their computers, this tutorial is meant to help you picture how your machine is responding when you input common commands into the terminal.

Your computer is basically a file storage system. Sure, you may have many applications installed. But where do they all live? In folders. Aka, directories. The basics of terminal usage involve navigating these directories.

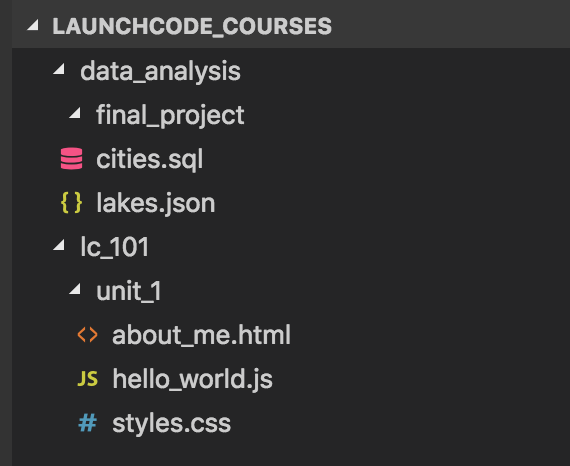

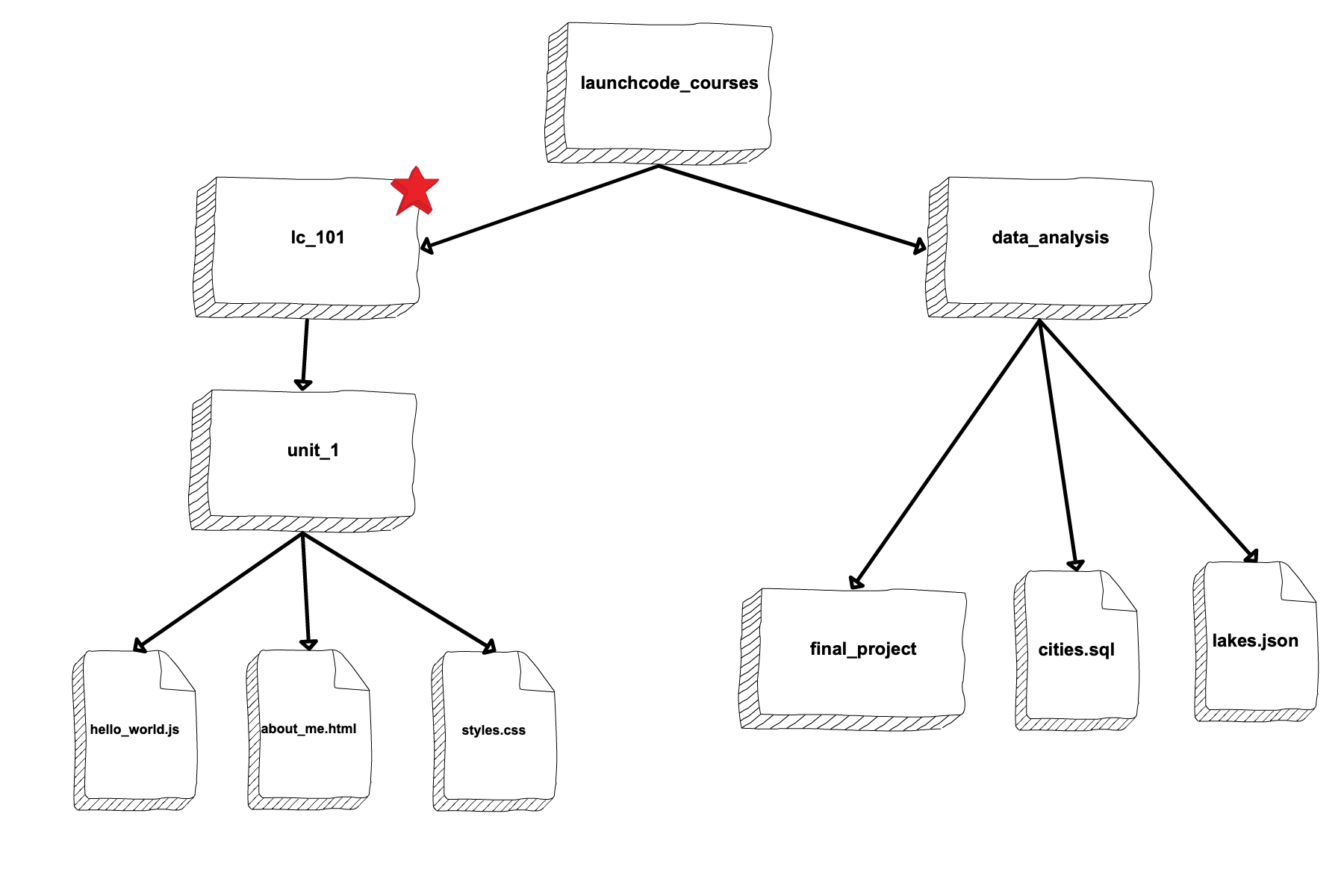

Let's take a look at a given project opened in your VSCode editor:

Sample file tree in VSCode¶

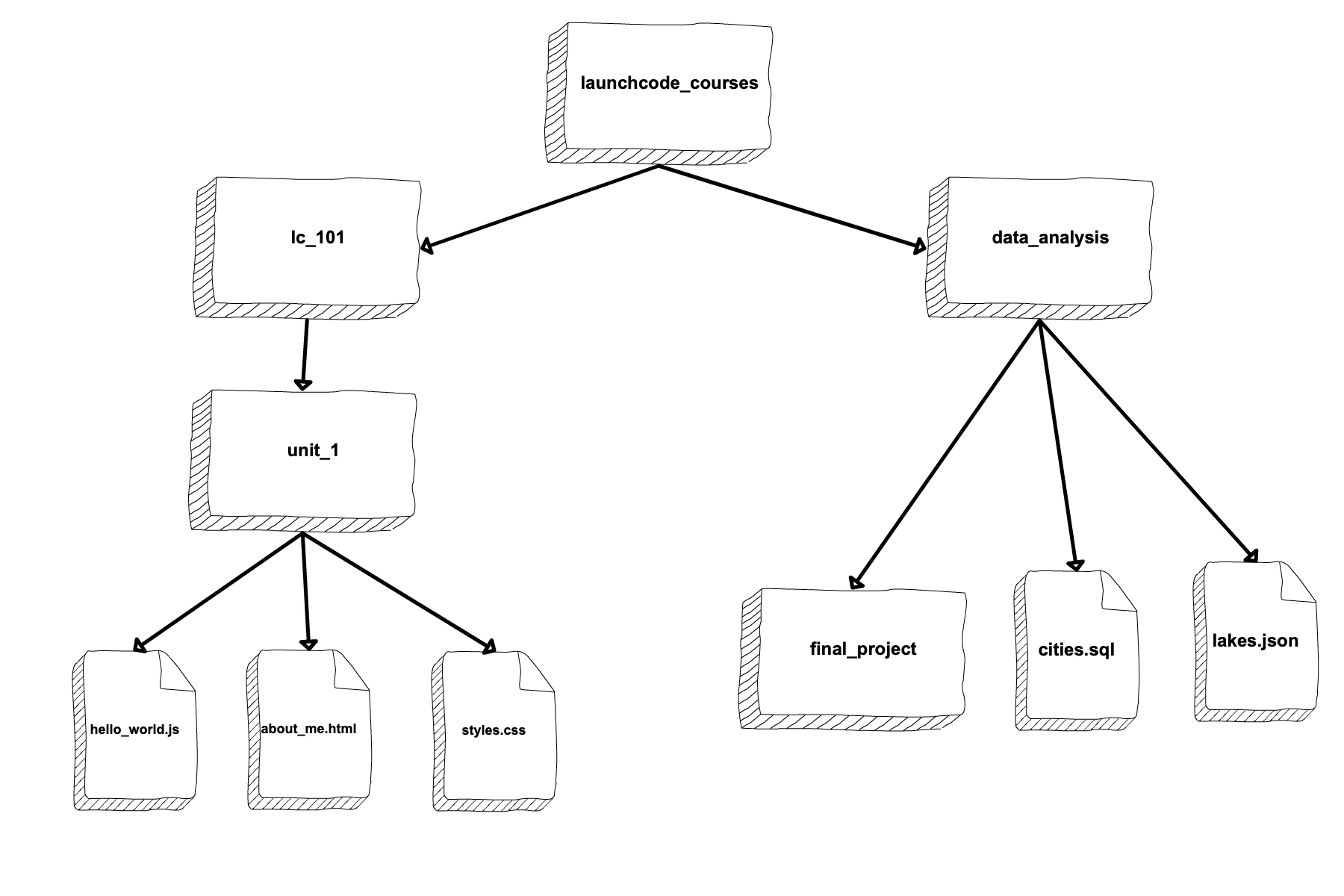

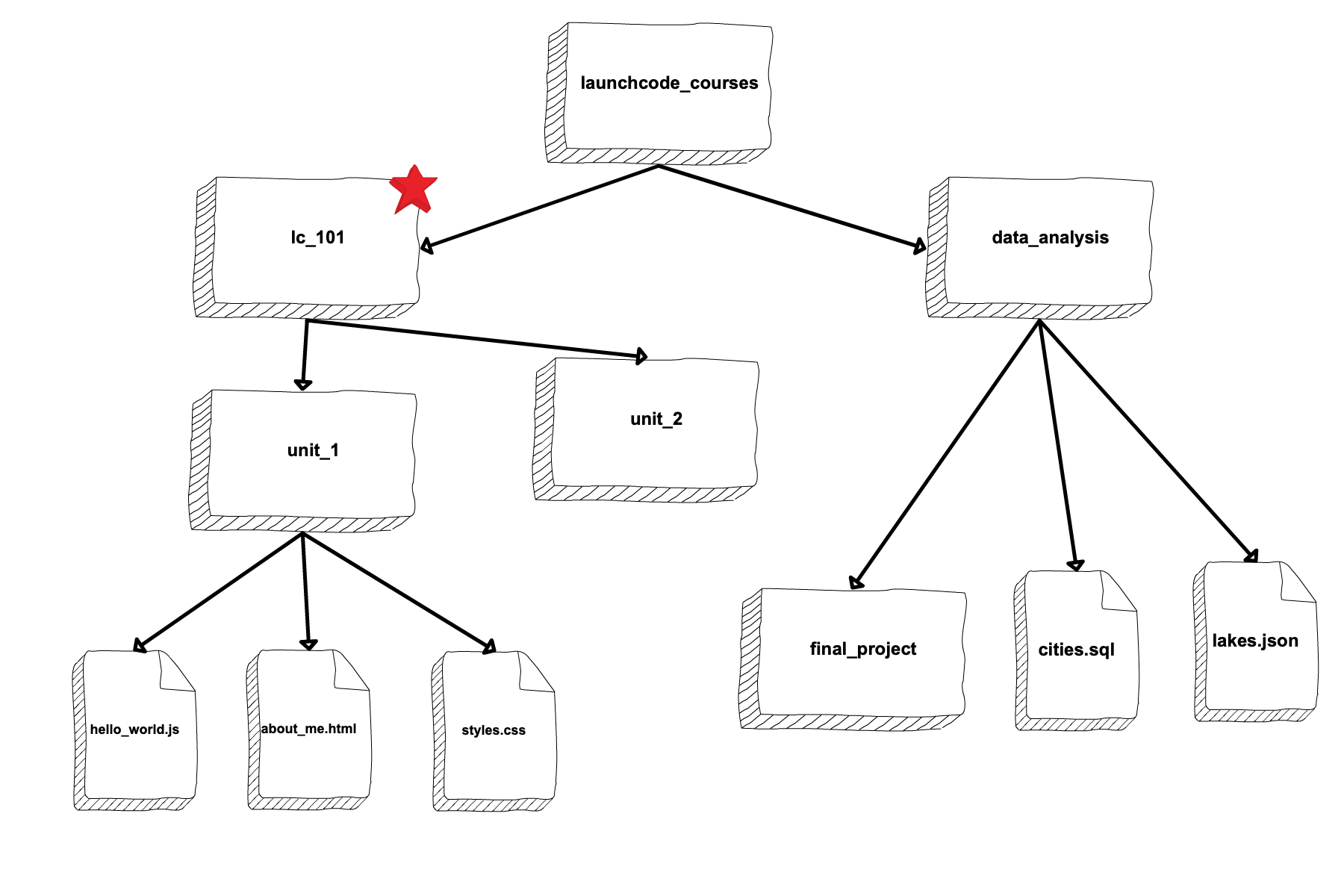

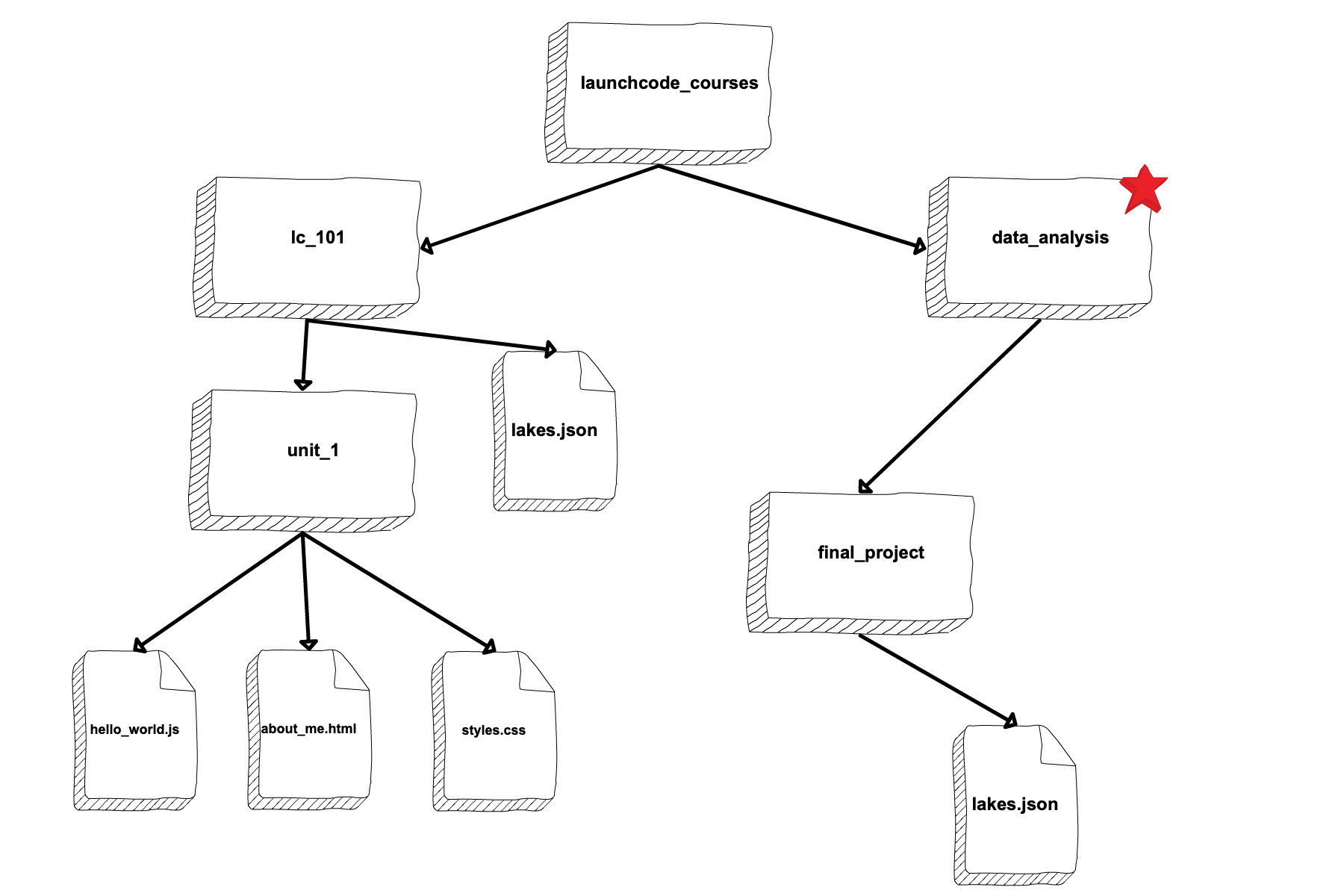

When working in the terminal, it can be helpful to think of yourself as physically inside of the project's file system. File trees, like the one above, are common visualization tools. Here's another map-like option for imagining your file system:

Sample file system map¶

We'll navigate through and edit this sample project folder for the remainder of this tutorial.

.)¶Imagining you are inside of this file system, . is a reference

to your location, or current directory.

Starting at the top directory, launchcode_courses, . represents

your current location.

Your current directory is launchcode_courses.¶

Here, your terminal will look something like this:

1computer:launchcode_courses user$

Most of what you see to the left of the command prompt symbol,

$ will be different on your machine. The basic structure here is

<machine_name>:<current_directory> <user_name>$.

Note

Some users choose to alter what they see before the command prompt.

For the purposes of this tutorial, we will simply use

<current_directory> $ as the prompt.

. itself is not a command. If you type only . into the terminal,

you're not really telling the machine to do anything just yet.

If you're curious, try it.

Note

Most commands require you to press Enter when you are ready to run.

You will probably see a somewhat cryptic message, like this:

1launchcode_courses $ .

2bash: .: filename argument required

3.: usage: . filename [arguments]

4launchcode_courses $

That's ok! Basically, we just entered an incomplete command. Our syntax

wasn't quite right. Keep reading and we'll see how to properly use ..

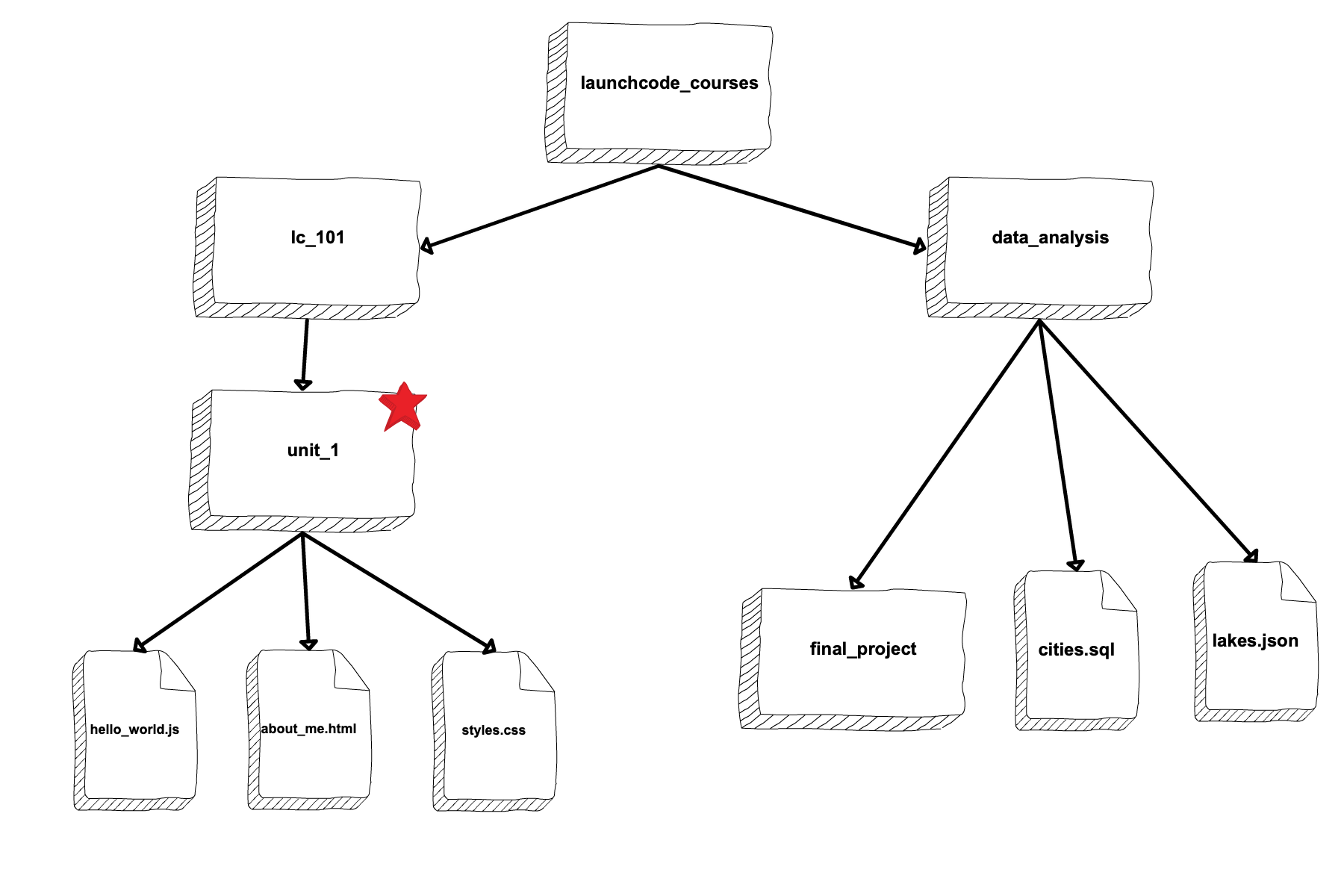

If you move into lc_101, . then refers to that directory. We'll

cover how to move locations in detail down in cd Command.

1launchcode_courses $ cd ./lc_101/

2lc_101 $

You may notice that the <current_directory> has updated but apart from that, the computer doesn't give us much response. This is quite common and is a reason why our file system visuals come in handy to help remind us what we're doing.

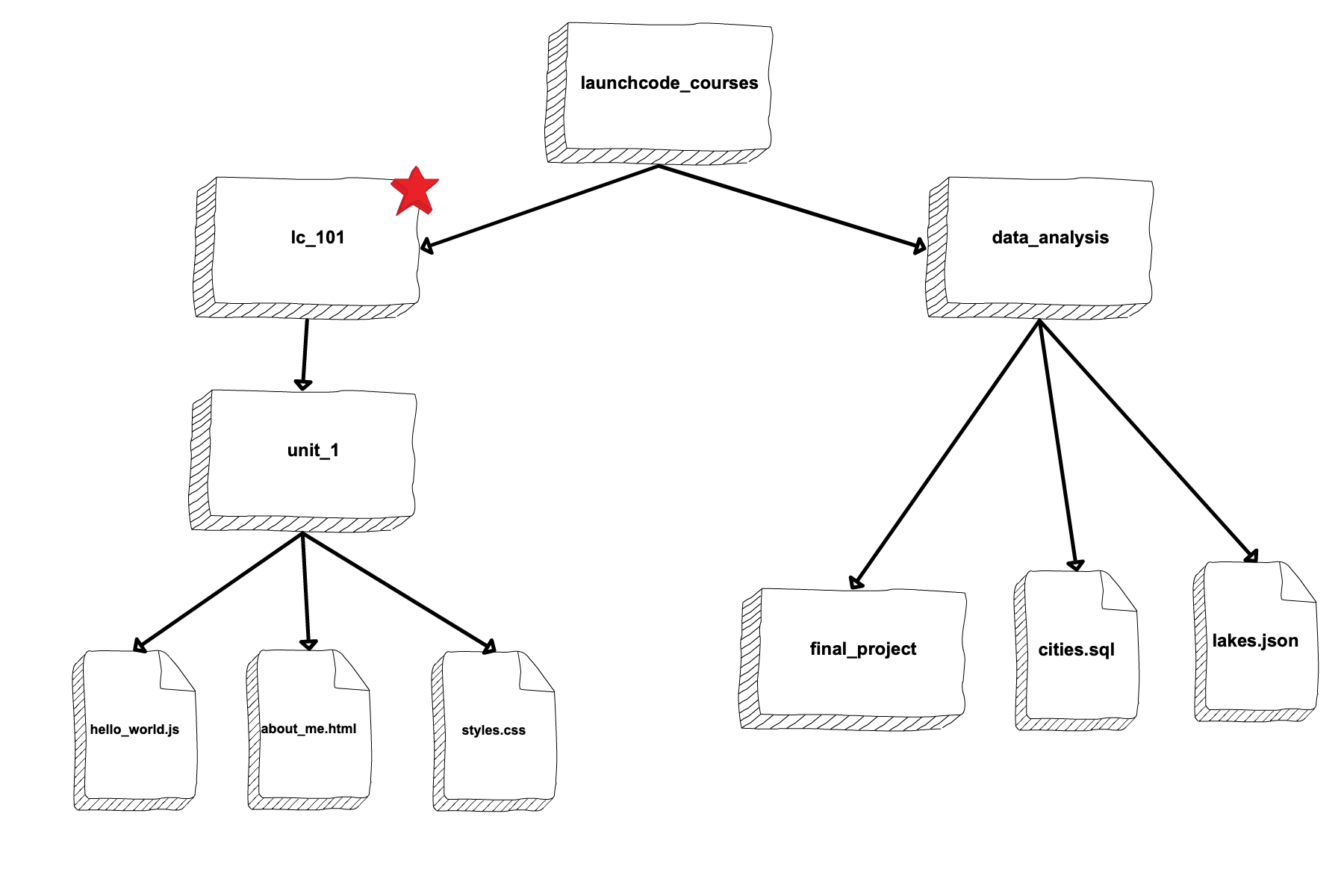

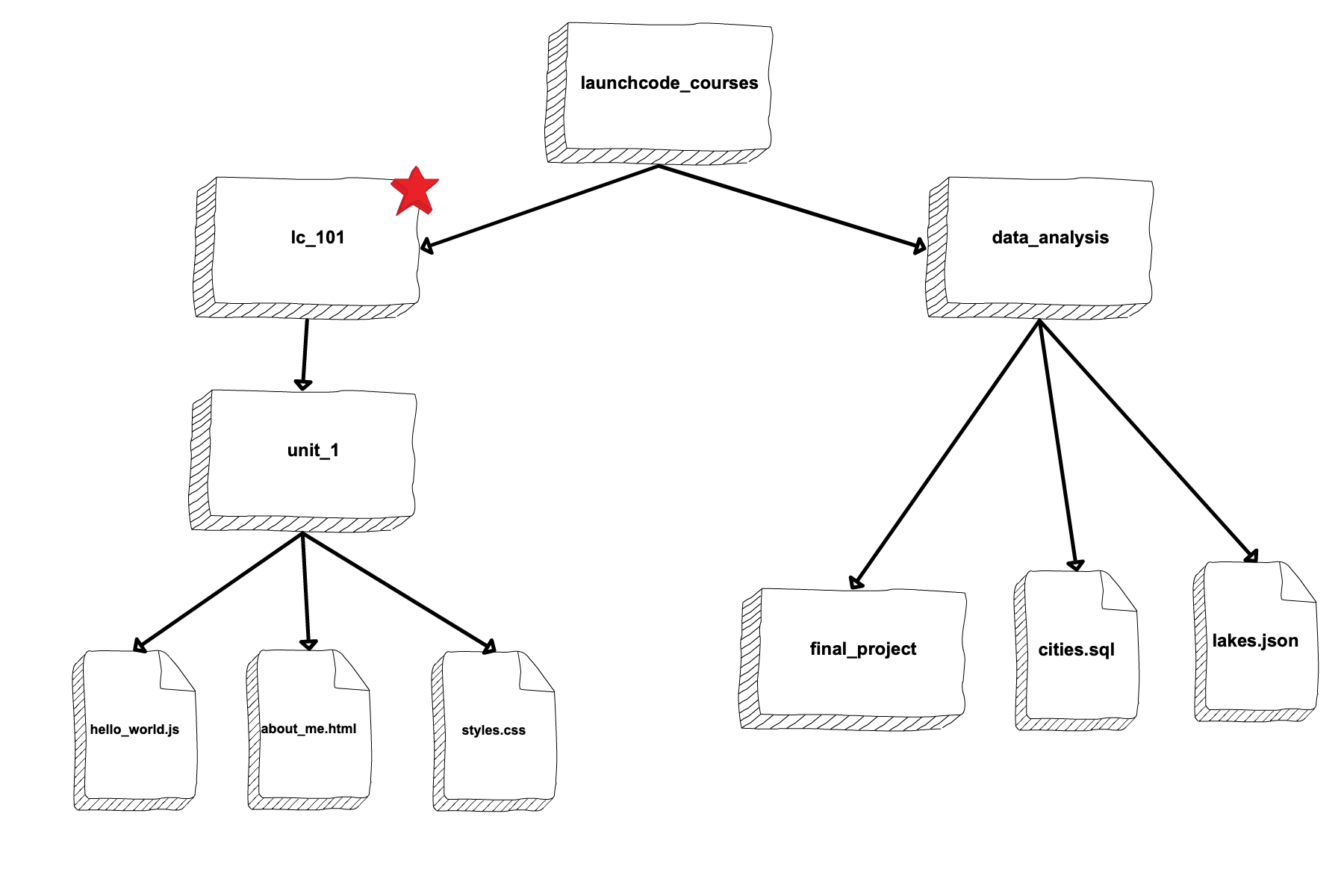

Back in our map, we've done this:

We're now in lc_101¶

..)¶.. is a reference to your parent directory, aka the directory

that CONTAINS your current location.

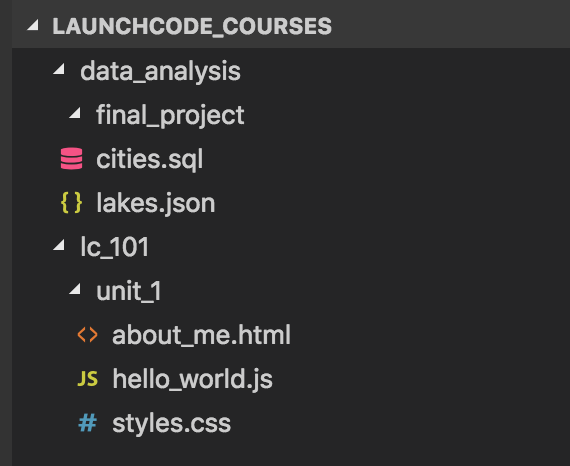

Remember the VSCode file tree? That containment structure is represented through indentation:

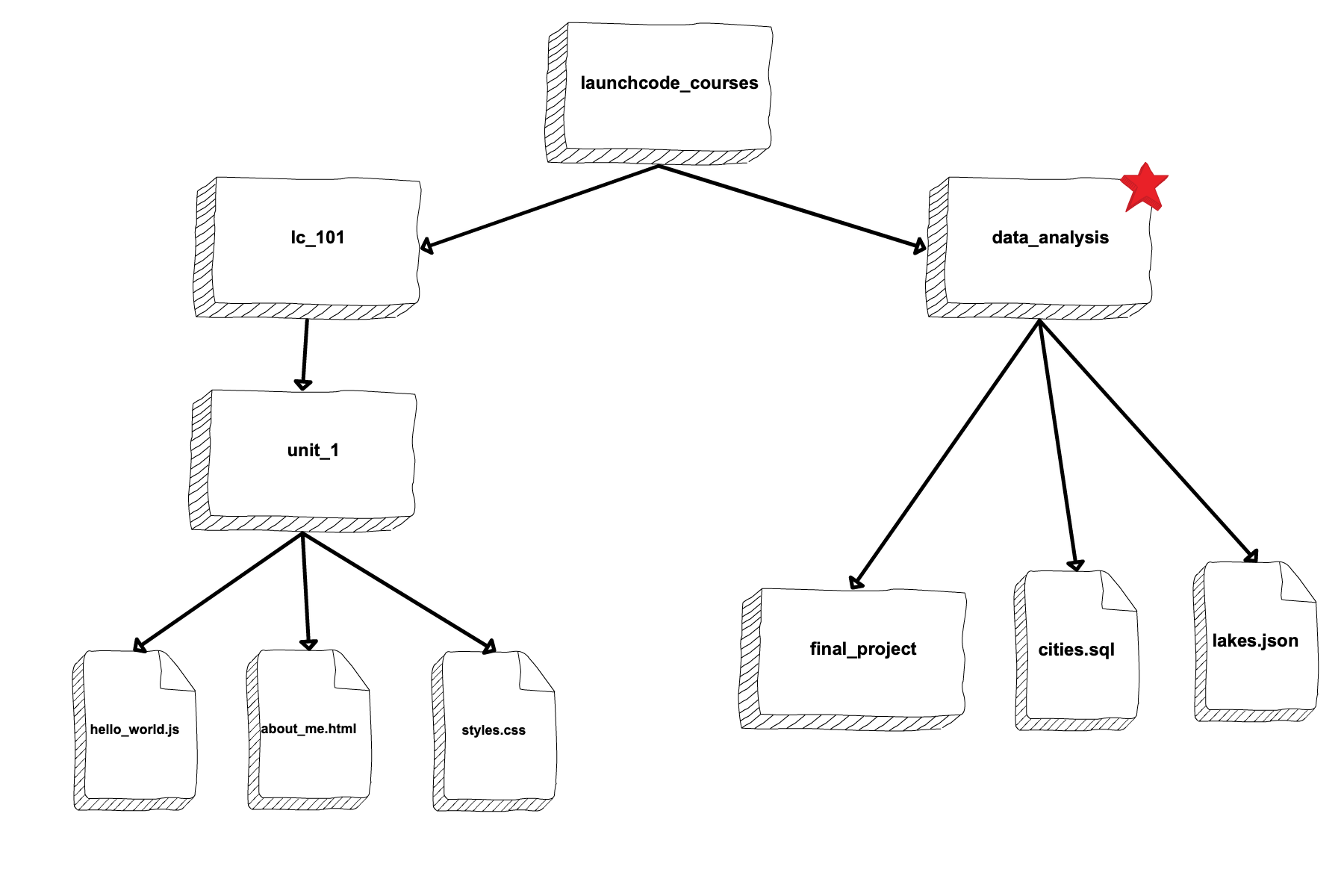

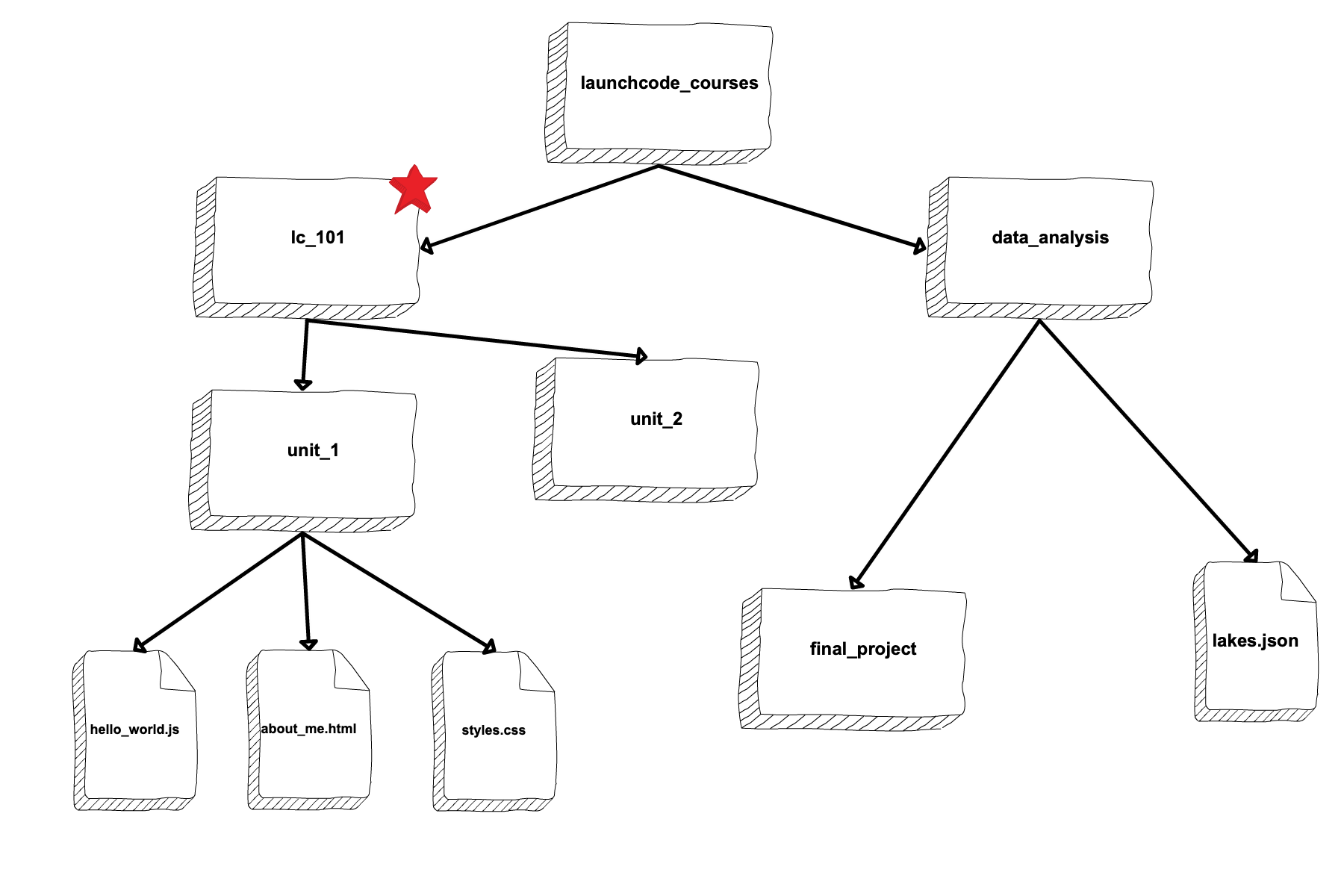

launchcode_courses contains data_analysis and lc_101.¶

By the end of the Current Directory (.), we found ourselves inside

of lc_101.

We're still in lc_101.¶

launchcode_courses is the parent directory of both the lc_101 and

data_analysis directories. While we're in lc_101, .. refers to

launchcode_courses.

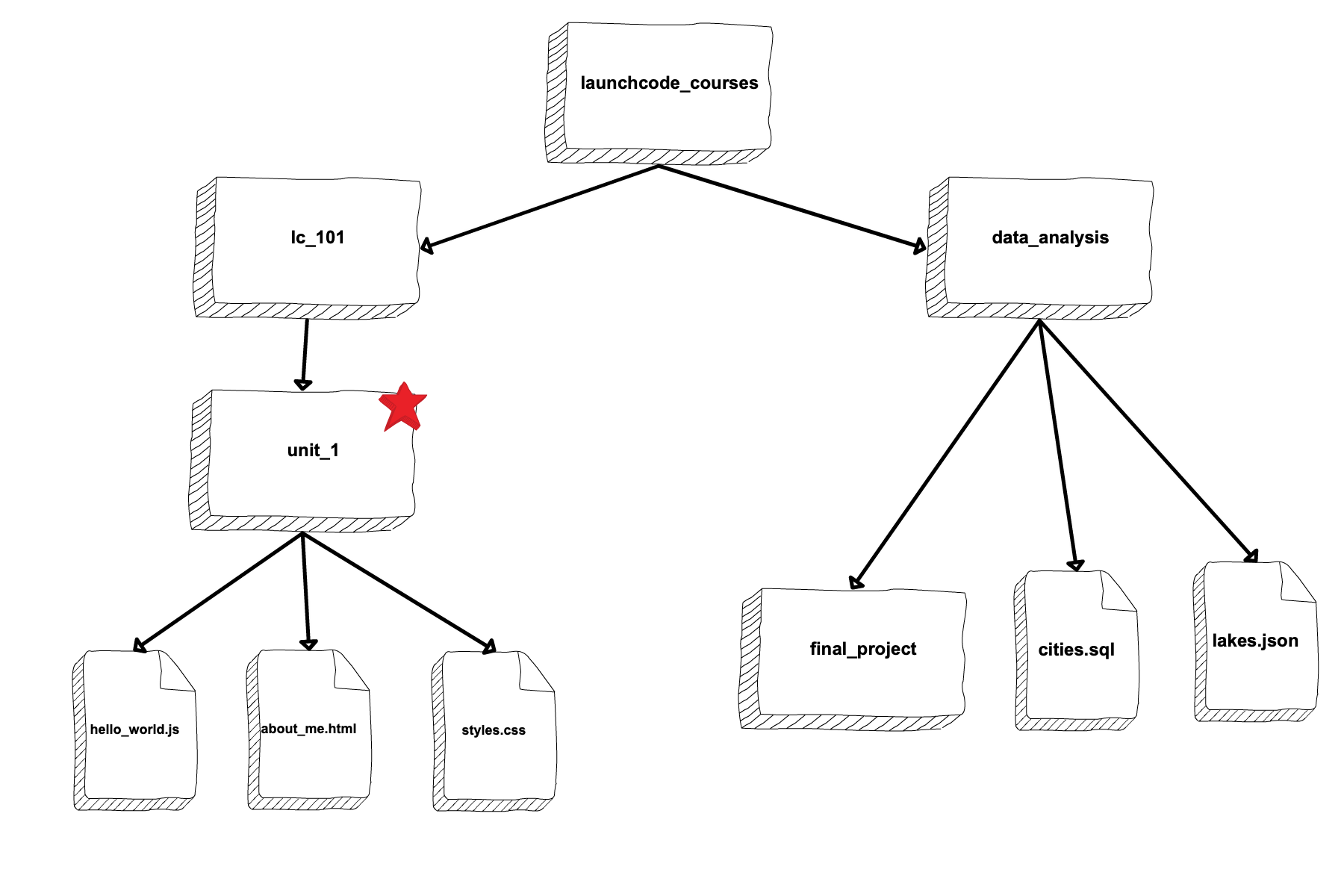

Moving further down into unit_1,

1lc_101 $ cd ./unit_1/

2unit_1 $

We're now in unit_1.¶

.. now refers to lc101.

../.. here refers to launchcode_courses.

Like . (Current Directory (.)), .. isn't a command itself, but

rather a notation. We're now ready to tackle our first command!

pwd Command¶Entering the pwd command in your terminal returns your current

location, aka your working directory.

1unit_1 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101/unit_1

3unit_1 $

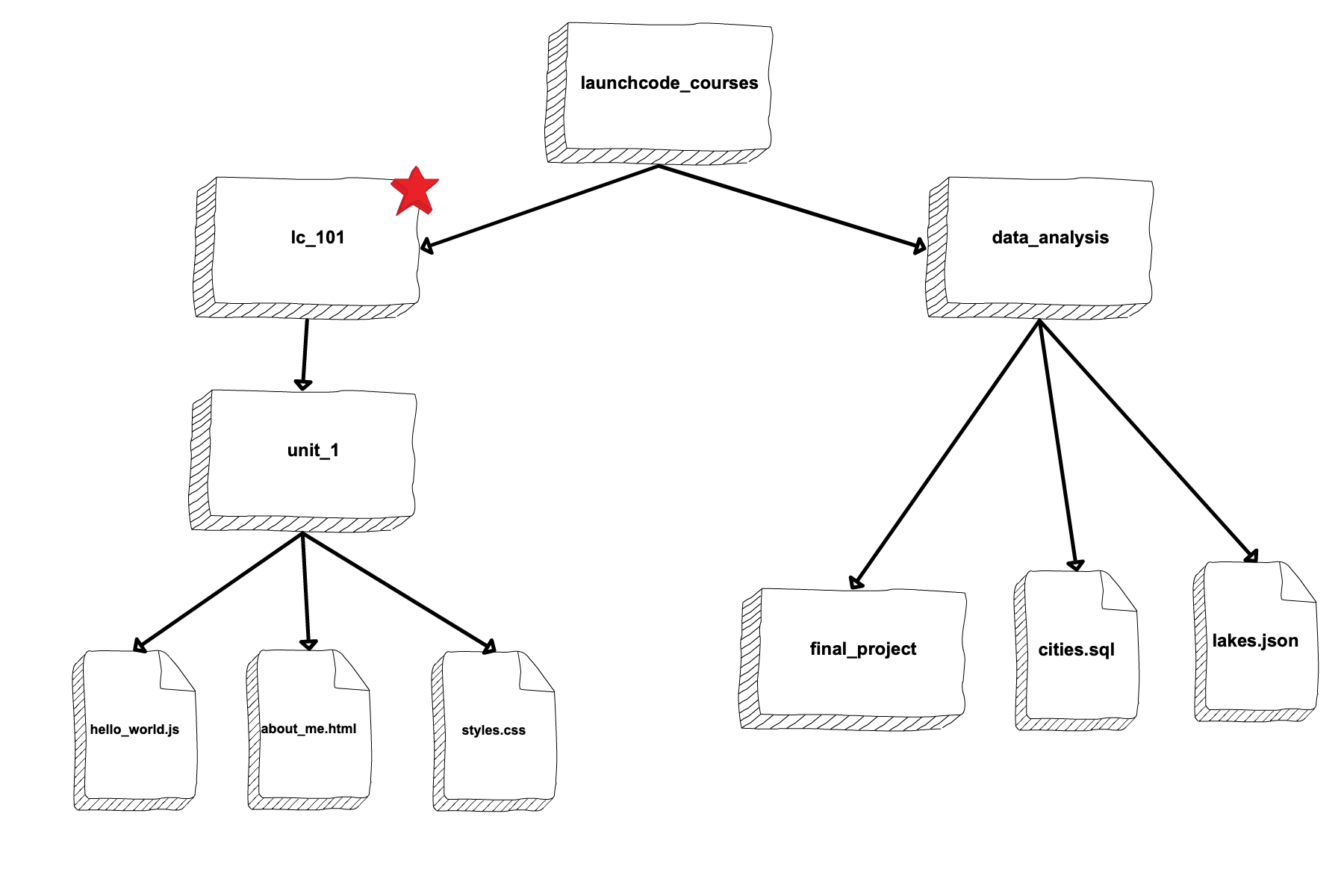

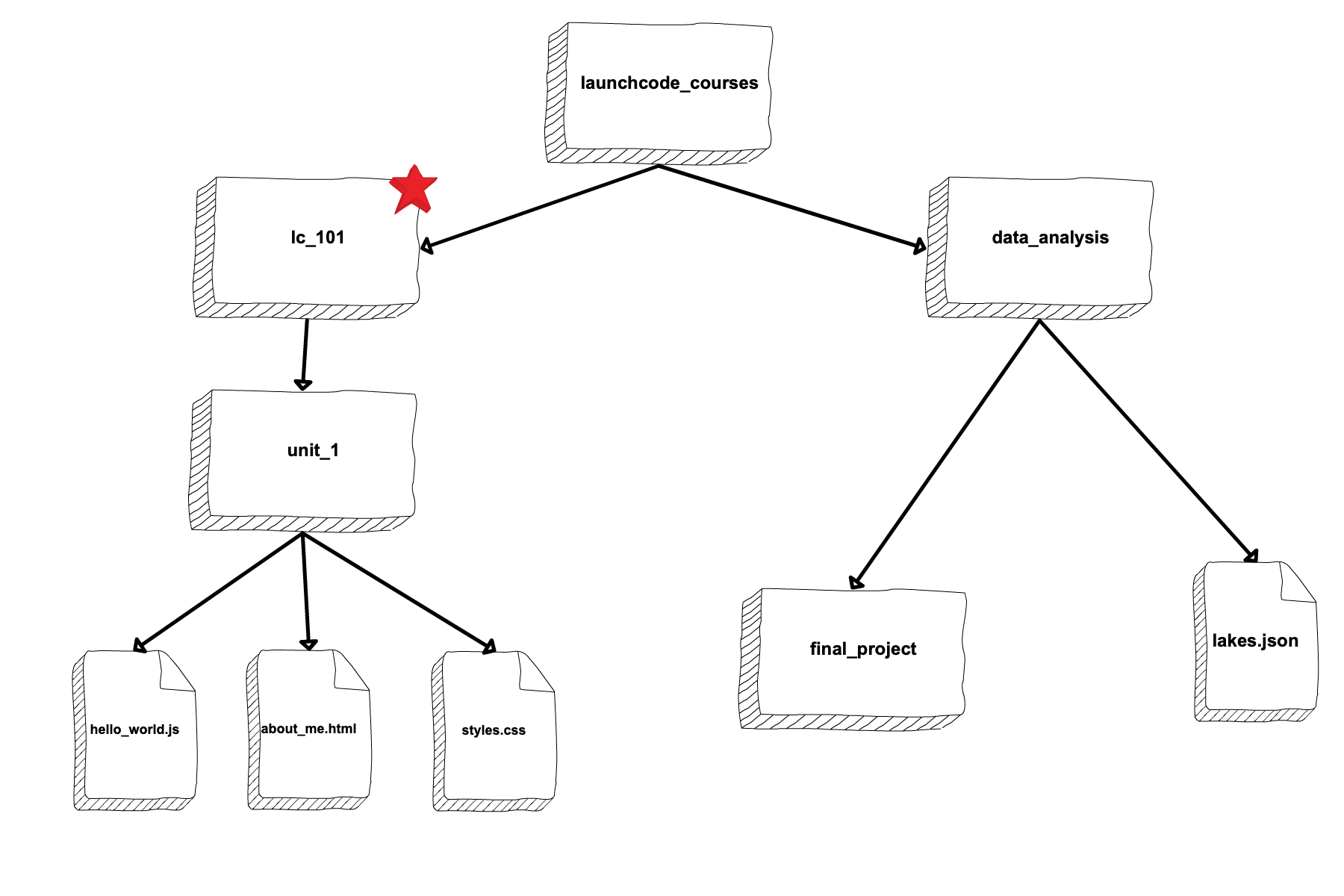

The working directory is another term for the current directory. Think of this command as like the 'You are here' star on our file maps.

We're still in unit_1.¶

You're basically just telling the computer to give you your current location.

This may seem basic, but this one is essential. You need to know your current

location when working in the terminal. A lot of beginner programmers simply

enter commands into the terminal without mind to where they are. pwd is

like a sanity check - a quick way to ensure that you know where you are and

what you're doing. It's the file system counterpart to Git's git status.

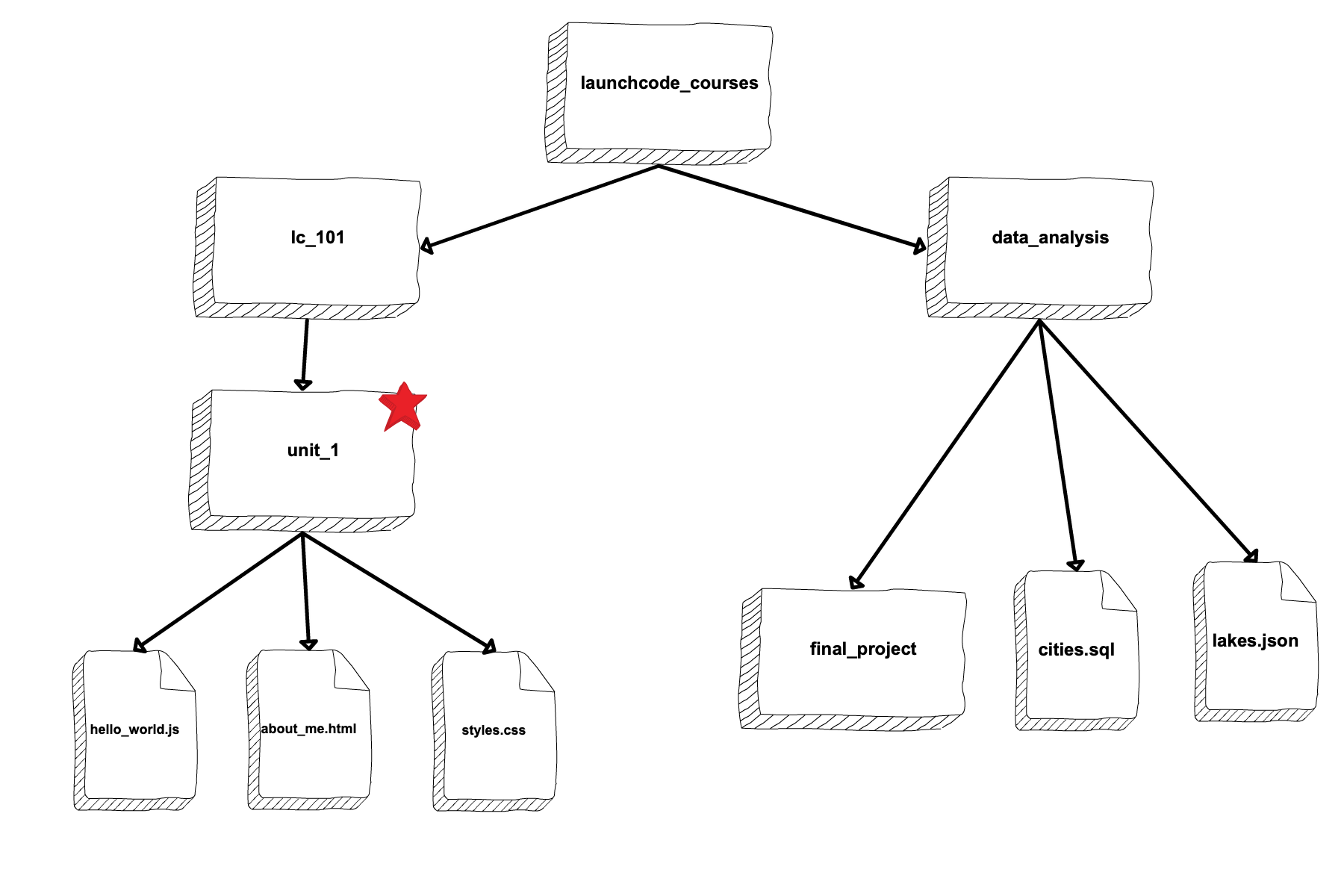

ls Command¶Entering the ls command in your terminal returns the contents of your

current directory. Recall, we're in unit_1.

We're still in unit_1.¶

1unit_1 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101/unit_1

3unit_1 $ ls

4about_me.html hello_world.js styles.css

All of that looks to be in order. Let's move back out into lc_101 and run

ls from there.

1unit_1 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101/unit_1

3unit_1 $ ls

4about_me.html hello_world.js styles.css

5unit_1 $ cd ..

6lc_101 $ pwd

7/launchcode_courses/lc_101

8lc_101 $ ls

9unit_1

10lc_101 $

Notice that pwd Command after we moved. Also pay attention that ls

only gives us a view one level deep. Now let's talk about how we move between

directories.

cd Command¶cd <path_name> relocates you to the provided path. We've seen it before,

now let's explore this command some more.

Remember, we're inside lc_101,

We're in lc_101.¶

To change directories to our Parent Directory (..), we run the following:

1lc_101 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ cd ..

4launchcode_courses $ pwd

5/launchcode_courses

6launchcode_courses $

It's pretty self-explanatory, now we're back in launchcode_courses.

We're back to launchcode_courses.¶

Not surprisingly, to go down into data_analysis, we run

cd ./data_analysis/

1launchcode_courses $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses

3launchcode_courses $ cd ./data_analysis/

4data_analysis $ pwd

5/launchcode_courses/data_analysis

6data_analysis $

We've made it to data_analysis.¶

Ok, so we know how to move one level above our current location (into our

parent directory) and how to move one level below our working directory. But

what if we wanted to get back to lc_101 from where we are now, in

data_analysis?

In order to move to a directory that is contained within the same parent as our working directory, we need to first go back up into the parent.

1data_analysis $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/data_analysis

3data_analysis $ cd lc_101

4bash: cd: lc_101: No such file or directory

5data_analysis $ pwd

6/launchcode_courses/data_analysis

7data_analysis $ cd ../lc_101/

8lc_101 $ pwd

9/launchcode_courses/lc_101

10lc_101 $

Do you see the faulty command? We tried running cd lc_101 from inside

data_analysis but the terminal did not recognize that path name from inside

the data_analysis directory.

We already know how to move to a parent directory, cd .., above we see how

we can move into a parent directory and down into one of its children all in

one command, cd ../lc_101/.

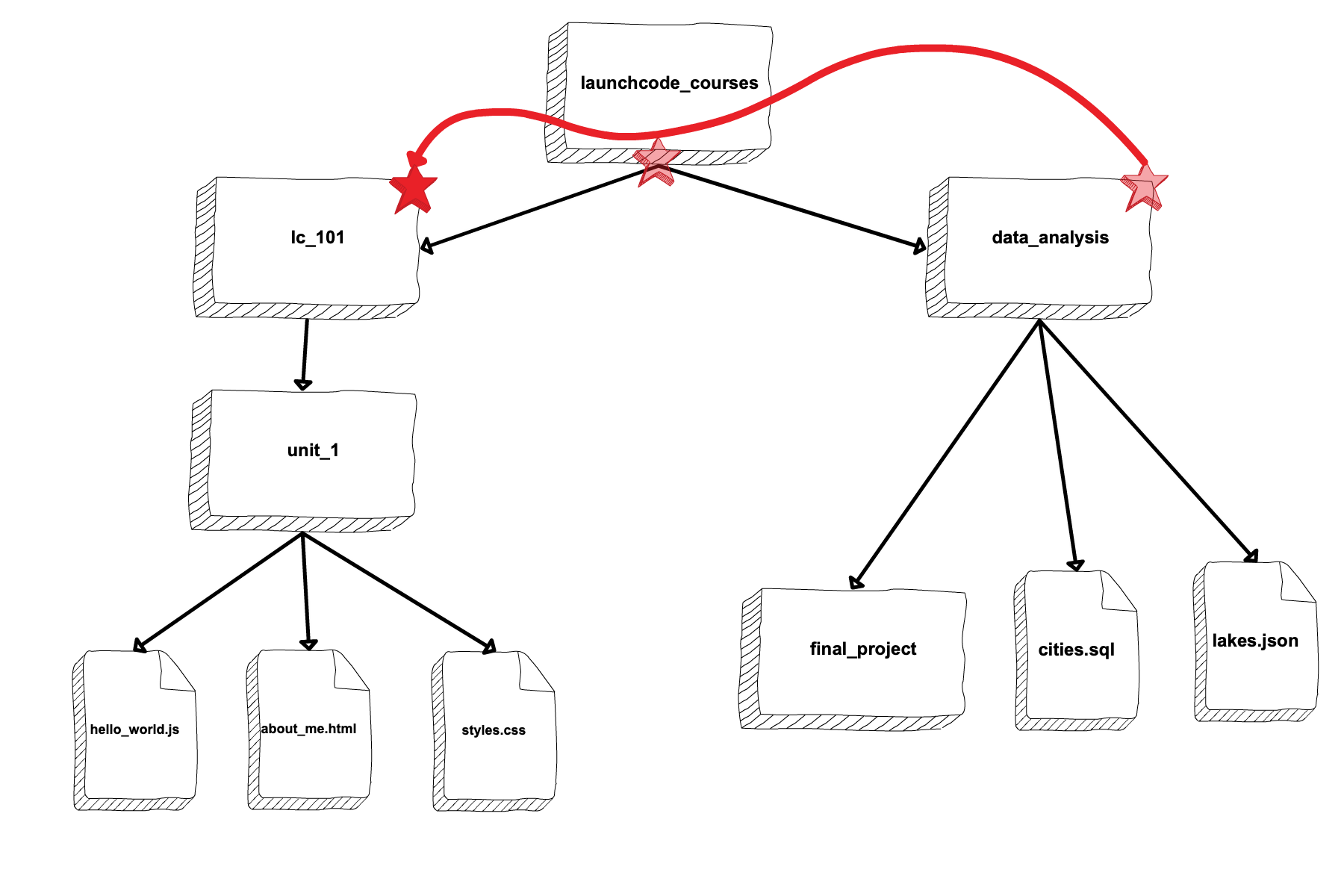

Here's a visual of where we've just been

Path to move to a peer directory.¶

For practice, let's go from our current spot in lc_101, down into

final_project.

1lc_101 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ cd ..

4launchcode_courses $ pwd

5/launchcode_courses

6launchcode_courses $ ls

7data_analysis lc_101

8launchcode_courses $ cd data_analysis/

9data_analysis $ ls

10cities.sql final_project lakes.json

11data_analysis $ cd final_project/

12final_project $ pwd

13launchcode_courses/data_analysis/final_project

14final_project $

Above, we check our location as we navigate to make sure we know where we're

going. If we're really confident though, we can accomplish moving from

lc_101 to final_project all in one go. Let's say we moved back to

lc_101 already.

1lc_101 $ pwd

2/launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ cd ../data_analysis/final_project/

4final_project $ pwd

5launchcode_courses/data_analysis/final_project

6final_project $

Are you starting to see how terminal navigation can get you places swiftly?

Let's do one more quick move for fun. To go back to lc_101,

all we need to do is cd ../../lc_101/.

1final_project $ pwd

2launchcode_courses/data_analysis/final_project

3final_project $ cd ../../lc_101/

4lc_101 $ pwd

5launchcode_courses/lc_101

6lc_101 $

Perhaps you noticed that the computer does not return anything to you after a

successful cd command. In the navigation samples above, we frequently rely

on the pwd Command and the ls Command to remind us where we

are and what paths are available to us.

mkdir Command¶mkdir <new_directory_name> creates a new directory inside your current

location.

We're in the lc_101 directory.

We're back in lc_101.¶

Here, let's create a directory for Unit 2 materials.

1lc_101 $ pwd

2launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ ls

4unit_1

5lc_101 $ mkdir unit_2

6lc_101 $ ls

7unit_1 unit_2

8lc_101 $

Again, the computer does not return anything to you after this command and simply responds ready to accept another prompt. But we can see from our helpful ls Command that a new directory has been created.

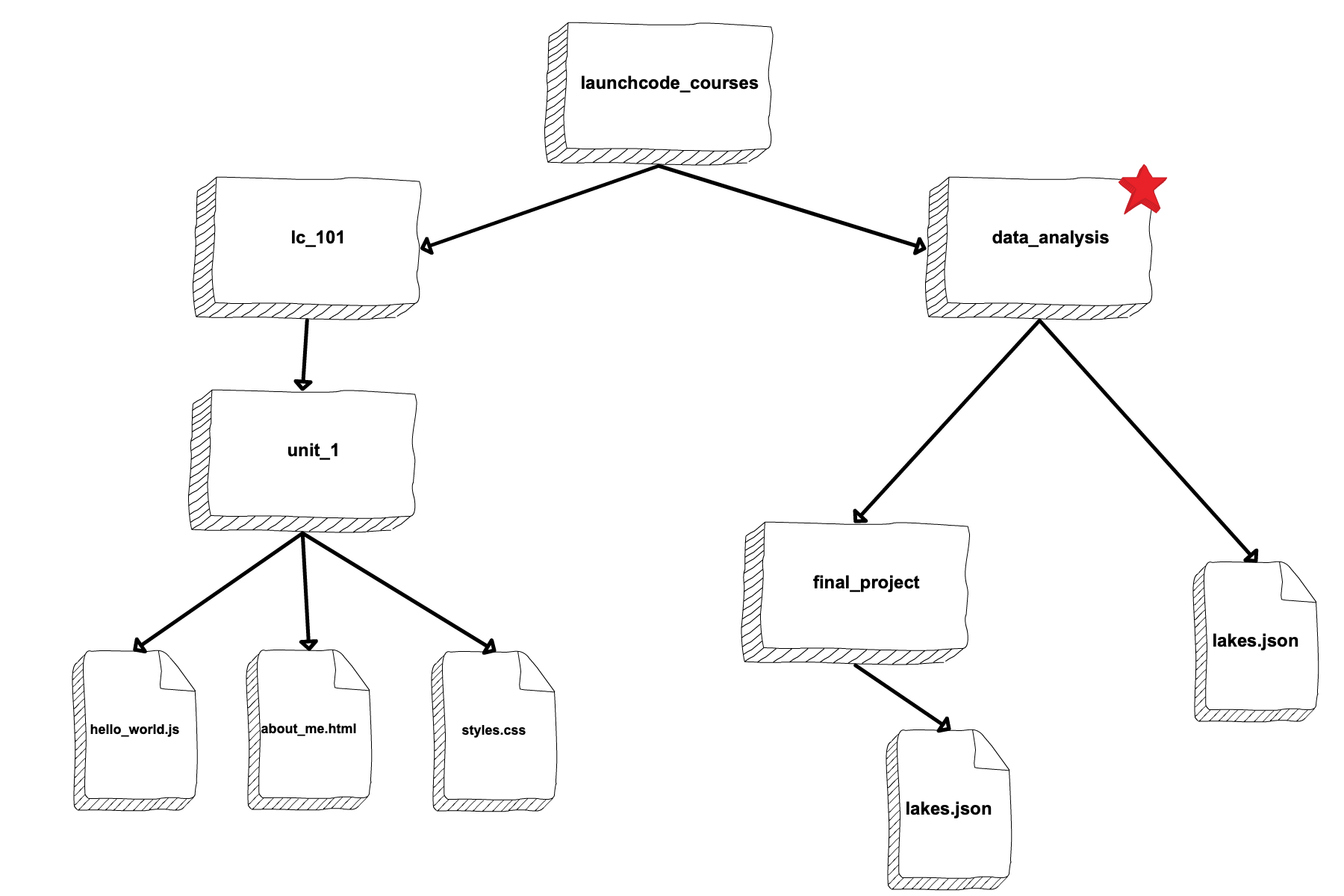

And we can visualize our changes like this:

mkdir creates a new directory¶

Note

While mkdir creates a new directory, it does not place us into that directory.

Additionally, we don't need to be in the parent of the newly created directory.

We can run mkdir from anywhere within the file system, as long as we use the

appropriate file path.

rm Command¶rm <item_to_remove> removes a given item from the file tree.

Let's say we decide we no longer need our cities.sql data. We can remove

it!

For fun - and practice! - let's remove it while we're still located in the

lc_101 directory.

1lc_101 $ pwd

2launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ rm ../data_analysis/cities.sql

4lc_101 $ pwd

5launchcode_courses/lc_101

6lc_101 $ ls ../data_analysis/

7final_project lakes.json

8lc_101 $

See what we did there? Instead of moving into the parent directory of

cities.sql, we just used the longer file path relative to our location in

lc_101. And to check that our rm command did what we expected? Well we

also checked that right from our spot in lc_101 with ls and a longer

path.

Here's the map of what we've done:

cities.sql is gone!¶

To remove a directory entry, rather than simply a file, requires an option

on the command. An option is an additional character, or set of characters,

added on the end of a text command to give the computer more instructions

related to your command. Options are usually indicated with a -. We'll talk

more about the presence of options in man Command.

A common method to remove a directory is to use the -r option, although

there are other choices.

Let's say we no longer want our unit_2 directory. We're still in

lc_101.

1lc_101 $ ls

2unit_1 unit_2

3lc_101 $ rm unit_2

4rm: unit_2: is a directory

5lc_101 $ ls

6unit_1 unit_2

7lc_101 $ rm -r unit_2

8lc_101 $ ls

9unit_1

10lc_101 $

Notice that simply using rm in line 3 returns a response telling us that

the item we've asked to remove is a directory. However, using rm -r in line

7 successfully removes the unit_2 directory.

Back in our map:

unit_2 is gone without a trace¶

cp Command¶cp <source_path> <target_path> copies the item at the source and puts it in

the target path. The item can be a file or whole directory and is named within

its own source path.

Take our sample file tree above. We're still in lc_101 and say we want to

copy our lakes.json file and place that copy inside the final_project

directory.

1lc_101 $ pwd

2launchcode_courses/lc_101

3lc_101 $ cd ../data_analysis/

4data_analysis $ pwd

5launchcode_courses/data_analysis

6data_analysis $ ls

7final_project lakes.json

8data_analysis $ cp ./lakes.json ./final_project/

9data_analysis $ ls

10final_project lakes.json

11data_analysis $ ls ./final_project/

12lakes.json

13data_analysis $

We didn't need to cd into data_analysis but since we are dealing with a

file contained within it, it made sense to do so. Once we ran our cp

command, we checked the contents of both data_analysis and

data_analysis/final_project to verify the copy was made.

And of course, now there are two lakes.json.

lakes.json double take¶

We can think of cp as basically copy and paste, since the target path is

included in the command.

mv Command¶mv <item_to_move> <target_path> moves an item to the provided target path.

The item being moved can be a single file or a whole directory. When referring

to the item being moved, its source path is required, just like the

cp Command.

Still in data_analysis, lets move data_analysis/lakes.json into

lc_101.

1data_analysis $ mv ./lakes.json ../lc_101/

2data_analysis $ pwd

3launchcode_courses/data_analysis

4data_analysis $ ls

5final_project

6data_analysis $ ls ../lc_101/

7lakes.json unit_1

8data_analysis $

As usual, we use ls to verify our results. Now our map looks like the

following:

mv moves one of the lakes.json.¶

touch Command¶touch <new_file_name> creates a new file.

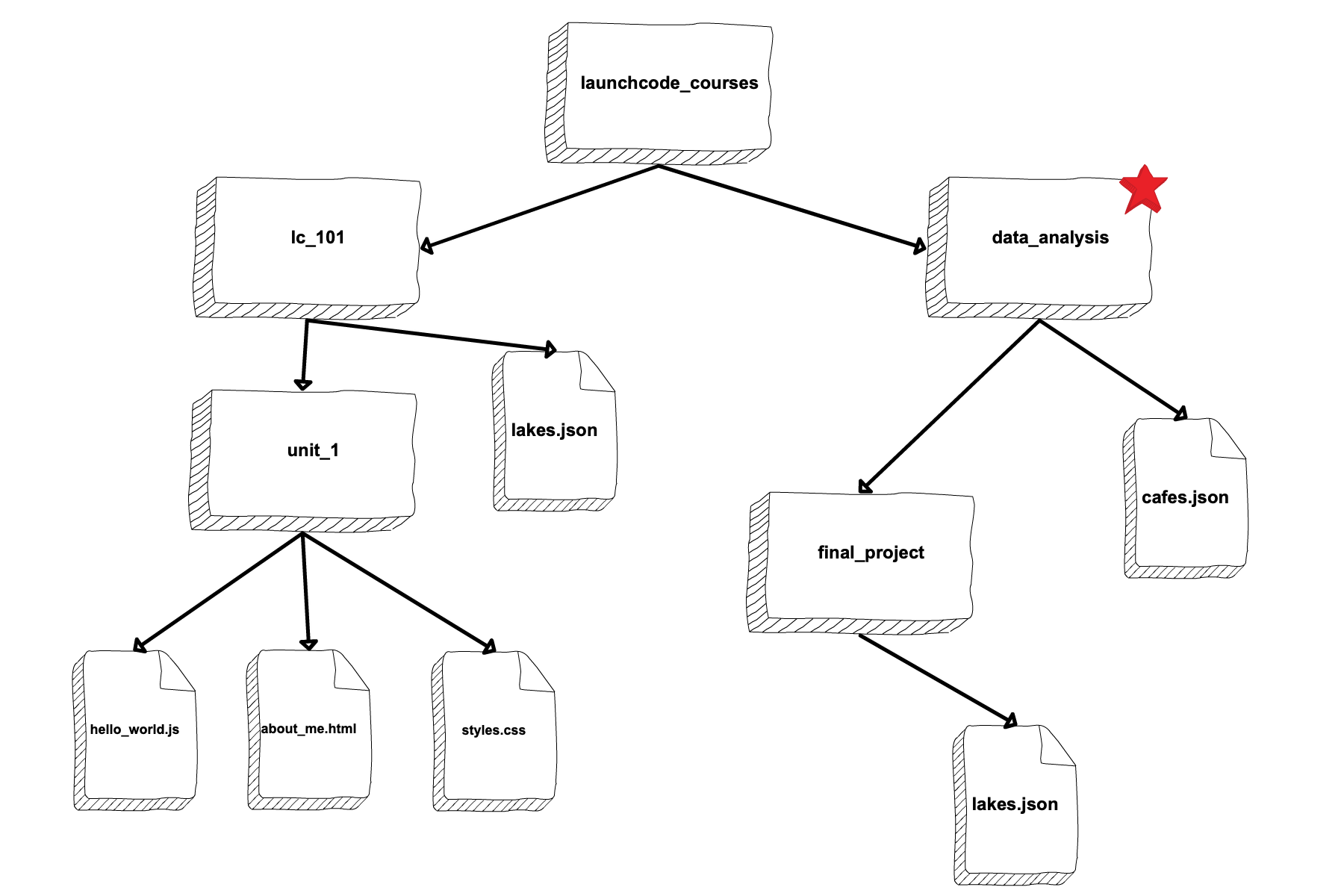

Back in data_analysis, lets add a new cafes.json file to our directory.

1data_analysis $ pwd

2launchcode_courses/data_analysis

3data_analysis $ ls

4final_project

5data_analysis $ touch cafes.json

6data_analysis $ ls

7cafes.json final_project

8data_analysis $

Here's what that gives us:

touch adds a file¶

clear Command¶clear wipes your terminal window of any previously run commands

and outputs in case you need a clean screen to think straight.

You probably won't encounter a scenario where you need to clear your terminal, but it can be a nice command to know if you're a minimalist.

There's no change to our file map to show when this command is run. And in the terminal window, as soon as enter is hit, the command results in what looks like a new window.

1data_analysis $

man Command¶man is your best friend. Running man <command> gives you a manual

entry of what that command does, what options it takes, and more

documentation than you could ever need. It's so thorough, it makes this

guide blush. Any command you think you may need, but you're not sure how

to use it, or maybe you want to do something specific and are wondering if

there's a specialized option for it, use man to get more info!

Practice looking up some of the commands you know; maybe you'll learn a new option or two!

Some other terminal stuff you should know when using the manual:

: at the

bottom of your terminal window. You can use your keyboard's arrow keys to

navigate the entry. If you reach the bottom of the entry,

you'll see a line that reads END.ctrl + c Details¶ctrl + c can be used to exit a running program.

Some programs take different commands to exit. ctrl + c is sometimes the command to quit a running program and other times used to prompt the running program for an different exit command.

q¶q is another command for exiting a running program. Notably, it is needed

to exit the man Command pages.